Convolutional (CNN) and Recurrent (RNN) Neural Networks

Dec 18, 2023

December 13 and 18

- Convolutional Neural Networks

- Readings and Videos:

- These lecture notes

- For a more in depth discussion on neural networks we recommend Goodfellow et al chapter 9. See also chapter 11 and 12 on practicalities and applications

- Reading suggestions for implementation of CNNs: Aurelien Geron's chapter 13.

- Video on Deep Learning

- Video on Convolutional Neural Networks from MIT

- Video on CNNs from Stanford

- See Michael Nielsen's Lectures

- "See Raschka, Liu and Mirjalili chapter 14":https://sebastianraschka.com/blog/2022/ml-pytorch-book.html"

Convolutional Neural Networks (recognizing images)

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were developed during the last decade of the previous century, with a focus on character recognition tasks. Nowadays, CNNs are a central element in the spectacular success of deep learning methods. The success in for example image classifications have made them a central tool for most machine learning practitioners.

CNNs are very similar to ordinary Neural Networks. They are made up of neurons that have learnable weights and biases. Each neuron receives some inputs, performs a dot product and optionally follows it with a non-linearity. The whole network still expresses a single differentiable score function: from the raw image pixels on one end to class scores at the other. And they still have a loss function (for example Softmax) on the last (fully-connected) layer and all the tips/tricks we developed for learning regular Neural Networks still apply (back propagation, gradient descent etc etc).

What is the Difference

CNN architectures make the explicit assumption that the inputs are images, which allows us to encode certain properties into the architecture. These then make the forward function more efficient to implement and vastly reduce the amount of parameters in the network.

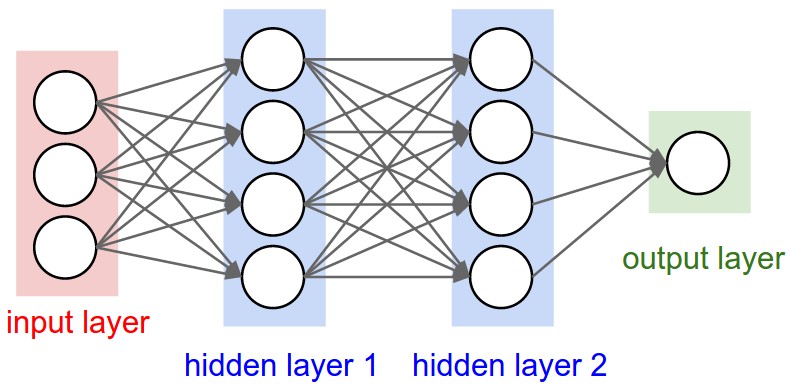

Neural Networks vs CNNs

Neural networks are defined as affine transformations, that is a vector is received as input and is multiplied with a matrix of so-called weights (our unknown paramters) to produce an output (to which a bias vector is usually added before passing the result through a nonlinear activation function). This is applicable to any type of input, be it an image, a sound clip or an unordered collection of features: whatever their dimensionality, their representation can always be flattened into a vector before the transformation.

Why CNNS for images, sound files, medical images from CT scans etc?

However, when we consider images, sound clips and many other similar kinds of data, these data have an intrinsic structure. More formally, they share these important properties:

- They are stored as multi-dimensional arrays (think of the pixels of a figure) .

- They feature one or more axes for which ordering matters (e.g., width and height axes for an image, time axis for a sound clip).

- One axis, called the channel axis, is used to access different views of the data (e.g., the red, green and blue channels of a color image, or the left and right channels of a stereo audio track).

These properties are not exploited when an affine transformation is applied; in fact, all the axes are treated in the same way and the topological information is not taken into account. Still, taking advantage of the implicit structure of the data may prove very handy in solving some tasks, like computer vision and speech recognition, and in these cases it would be best to preserve it. This is where discrete convolutions come into play.

A discrete convolution is a linear transformation that preserves this notion of ordering. It is sparse (only a few input units contribute to a given output unit) and reuses parameters (the same weights are applied to multiple locations in the input).

Regular NNs don’t scale well to full images

As an example, consider an image of size \( 32\times 32\times 3 \) (32 wide, 32 high, 3 color channels), so a single fully-connected neuron in a first hidden layer of a regular Neural Network would have \( 32\times 32\times 3 = 3072 \) weights. This amount still seems manageable, but clearly this fully-connected structure does not scale to larger images. For example, an image of more respectable size, say \( 200\times 200\times 3 \), would lead to neurons that have \( 200\times 200\times 3 = 120,000 \) weights.

We could have several such neurons, and the parameters would add up quickly! Clearly, this full connectivity is wasteful and the huge number of parameters would quickly lead to possible overfitting.

Figure 1: A regular 3-layer Neural Network.

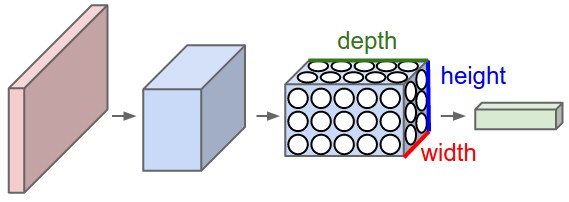

3D volumes of neurons

Convolutional Neural Networks take advantage of the fact that the input consists of images and they constrain the architecture in a more sensible way.

In particular, unlike a regular Neural Network, the layers of a CNN have neurons arranged in 3 dimensions: width, height, depth. (Note that the word depth here refers to the third dimension of an activation volume, not to the depth of a full Neural Network, which can refer to the total number of layers in a network.)

To understand it better, the above example of an image with an input volume of activations has dimensions \( 32\times 32\times 3 \) (width, height, depth respectively).

The neurons in a layer will only be connected to a small region of the layer before it, instead of all of the neurons in a fully-connected manner. Moreover, the final output layer could for this specific image have dimensions \( 1\times 1 \times 10 \), because by the end of the CNN architecture we will reduce the full image into a single vector of class scores, arranged along the depth dimension.

Figure 2: A CNN arranges its neurons in three dimensions (width, height, depth), as visualized in one of the layers. Every layer of a CNN transforms the 3D input volume to a 3D output volume of neuron activations. In this example, the red input layer holds the image, so its width and height would be the dimensions of the image, and the depth would be 3 (Red, Green, Blue channels).

Layers used to build CNNs

A simple CNN is a sequence of layers, and every layer of a CNN transforms one volume of activations to another through a differentiable function. We use three main types of layers to build CNN architectures: Convolutional Layer, Pooling Layer, and Fully-Connected Layer (exactly as seen in regular Neural Networks). We will stack these layers to form a full CNN architecture.

A simple CNN for image classification could have the architecture:

- INPUT (\( 32\times 32 \times 3 \)) will hold the raw pixel values of the image, in this case an image of width 32, height 32, and with three color channels R,G,B.

- CONV (convolutional )layer will compute the output of neurons that are connected to local regions in the input, each computing a dot product between their weights and a small region they are connected to in the input volume. This may result in volume such as \( [32\times 32\times 12] \) if we decided to use 12 filters.

- RELU layer will apply an elementwise activation function, such as the \( max(0,x) \) thresholding at zero. This leaves the size of the volume unchanged (\( [32\times 32\times 12] \)).

- POOL (pooling) layer will perform a downsampling operation along the spatial dimensions (width, height), resulting in volume such as \( [16\times 16\times 12] \).

- FC (i.e. fully-connected) layer will compute the class scores, resulting in volume of size \( [1\times 1\times 10] \), where each of the 10 numbers correspond to a class score, such as among the 10 categories of the MNIST images we considered above . As with ordinary Neural Networks and as the name implies, each neuron in this layer will be connected to all the numbers in the previous volume.

Transforming images

CNNs transform the original image layer by layer from the original pixel values to the final class scores.

Observe that some layers contain parameters and other don’t. In particular, the CNN layers perform transformations that are a function of not only the activations in the input volume, but also of the parameters (the weights and biases of the neurons). On the other hand, the RELU/POOL layers will implement a fixed function. The parameters in the CONV/FC layers will be trained with gradient descent so that the class scores that the CNN computes are consistent with the labels in the training set for each image.

CNNs in brief

In summary:

- A CNN architecture is in the simplest case a list of Layers that transform the image volume into an output volume (e.g. holding the class scores)

- There are a few distinct types of Layers (e.g. CONV/FC/RELU/POOL are by far the most popular)

- Each Layer accepts an input 3D volume and transforms it to an output 3D volume through a differentiable function

- Each Layer may or may not have parameters (e.g. CONV/FC do, RELU/POOL don’t)

- Each Layer may or may not have additional hyperparameters (e.g. CONV/FC/POOL do, RELU doesn’t)

For more material on convolutional networks, we strongly recommend the course CS231 which is taught at Stanford University (consistently ranked as one of the top computer science programs in the world). Michael Nielsen's book is a must read, in particular chapter 6 which deals with CNNs.

The textbook by Goodfellow et al, see chapter 9 contains an in depth discussion as well.

Key Idea

A dense neural network is representd by an affine operation (like matrix-matrix multiplication) where all parameters are included.

The key idea in CNNs for say imaging is that in images neighbor pixels tend to be related! So we connect only neighboring neurons in the input instead of connecting all with the first hidden layer.

We say we perform a filtering (convolution is the mathematical operation).

Mathematics of CNNs

The mathematics of CNNs is based on the mathematical operation of convolution. In mathematics (in particular in functional analysis), convolution is represented by mathematical operation (integration, summation etc) on two function in order to produce a third function that expresses how the shape of one gets modified by the other. Convolution has a plethora of applications in a variety of disciplines, spanning from statistics to signal processing, computer vision, solutions of differential equations,linear algebra, engineering, and yes, machine learning.

Mathematically, convolution is defined as follows (one-dimensional example): Let us define a continuous function \( y(t) \) given by

$$

y(t) = \int x(a) w(t-a) da,

$$

where \( x(a) \) represents a so-called input and \( w(t-a) \) is normally called the weight function or kernel.

The above integral is written in a more compact form as

$$

y(t) = \left(x * w\right)(t).

$$

The discretized version reads

$$

y(t) = \sum_{a=-\infty}^{a=\infty}x(a)w(t-a).

$$

Computing the inverse of the above convolution operations is known as deconvolution.

How can we use this? And what does it mean? Let us study some familiar examples first.

Convolution Examples: Polynomial multiplication

We have already met such an example in project 1 when we tried to set up the design matrix for a two-dimensional function. This was an example of polynomial multiplication. Let us recast such a problem in terms of the convolution operation. Let us look a the following polynomials to second and third order, respectively:

$$

p(t) = \alpha_0+\alpha_1 t+\alpha_2 t^2,

$$

and

$$

s(t) = \beta_0+\beta_1 t+\beta_2 t^2+\beta_3 t^3.

$$

The polynomial multiplication gives us a new polynomial of degree \( 5 \)

$$

z(t) = \delta_0+\delta_1 t+\delta_2 t^2+\delta_3 t^3+\delta_4 t^4+\delta_5 t^5.

$$

Efficient Polynomial Multiplication

Computing polynomial products can be implemented efficiently if we rewrite the more brute force multiplications using convolution. We note first that the new coefficients are given as

$$

\begin{split}

\delta_0=&\alpha_0\beta_0\\

\delta_1=&\alpha_1\beta_0+\alpha_1\beta_0\\

\delta_2=&\alpha_0\beta_2+\alpha_1\beta_1+\alpha_2\beta_0\\

\delta_3=&\alpha_1\beta_2+\alpha_2\beta_1+\alpha_0\beta_3\\

\delta_4=&\alpha_2\beta_2+\alpha_1\beta_3\\

\delta_5=&\alpha_2\beta_3.\\

\end{split}

$$

We note that \( \alpha_i=0 \) except for \( i\in \left\{0,1,2\right\} \) and \( \beta_i=0 \) except for \( i\in\left\{0,1,2,3\right\} \).

We can then rewrite the coefficients \( \delta_j \) using a discrete convolution as

$$

\delta_j = \sum_{i=-\infty}^{i=\infty}\alpha_i\beta_{j-i}=(\alpha * \beta)_j,

$$

or as a double sum with restriction \( l=i+j \)

$$

\delta_l = \sum_{ij}\alpha_i\beta_{j}.

$$

Do you see a potential drawback with these equations?

A more efficient way of coding the above Convolution

Since we only have a finite number of \( \alpha \) and \( \beta \) values which are non-zero, we can rewrite the above convolution expressions as a matrix-vector multiplication

$$

\boldsymbol{\delta}=\begin{bmatrix}\alpha_0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

\alpha_1 & \alpha_0 & 0 & 0 \\

\alpha_2 & \alpha_1 & \alpha_0 & 0 \\

0 & \alpha_2 & \alpha_1 & \alpha_0 \\

0 & 0 & \alpha_2 & \alpha_1 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & \alpha_2

\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \beta_0 \\ \beta_1 \\ \beta_2 \\ \beta_3\end{bmatrix}.

$$

The process is commutative and we can easily see that we can rewrite the multiplication in terms of a matrix holding \( \beta \) and a vector holding \( \alpha \). In this case we have

$$

\boldsymbol{\delta}=\begin{bmatrix}\beta_0 & 0 & 0 \\

\beta_1 & \beta_0 & 0 \\

\beta_2 & \beta_1 & \beta_0 \\

\beta_3 & \beta_2 & \beta_1 \\

0 & \beta_3 & \beta_2 \\

0 & 0 & \beta_3

\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} \alpha_0 \\ \alpha_1 \\ \alpha_2\end{bmatrix}.

$$

Note that the use of these matrices is for mathematical purposes only and not implementation purposes. When implementing the above equation we do not encode (and allocate memory) the matrices explicitely. We rather code the convolutions in the minimal memory footprint that they require.

Does the number of floating point operations change here when we use the commutative property?

The above matrices are examples of so-called Toeplitz matrices. A Toeplitz matrix is a matrix in which each descending diagonal from left to right is constant. For instance the last matrix, which we rewrite as

$$

\boldsymbol{A}=\begin{bmatrix}a_0 & 0 & 0 \\

a_1 & a_0 & 0 \\

a_2 & a_1 & a_0 \\

a_3 & a_2 & a_1 \\

0 & a_3 & a_2 \\

0 & 0 & a_3

\end{bmatrix},

$$

with elements \( a_{ii}=a_{i+1,j+1}=a_{i-j} \) is an example of a Toeplitz matrix. Such a matrix does not need to be a square matrix. Toeplitz matrices are also closely connected with Fourier series discussed below, because the multiplication operator by a trigonometric polynomial, compressed to a finite-dimensional space, can be represented by such a matrix. The example above shows that we can represent linear convolution as multiplication of a Toeplitz matrix by a vector.

Convolution Examples: Principle of Superposition and Periodic Forces (Fourier Transforms)

For problems with so-called harmonic oscillations, given by for example the following differential equation

$$

m\frac{d^2x}{dt^2}+\eta\frac{dx}{dt}+x(t)=F(t),

$$

where \( F(t) \) is an applied external force acting on the system (often called a driving force), one can use the theory of Fourier transformations to find the solutions of this type of equations.

If one has several driving forces, \( F(t)=\sum_n F_n(t) \), one can find the particular solution \( x_{pn}(t) \) to the above differential equation for each \( F_n \). The particular solution for the entire driving force is then given by a series like

$$

\begin{equation}

x_p(t)=\sum_nx_{pn}(t).

\tag{1}

\end{equation}

$$

This is known as the principle of superposition. It only applies when the homogenous equation is linear. Superposition is especially useful when \( F(t) \) can be written as a sum of sinusoidal terms, because the solutions for each sinusoidal (sine or cosine) term is analytic.

Driving forces are often periodic, even when they are not sinusoidal. Periodicity implies that for some time \( t \) our function repeats itself periodically after a period \( \tau \), that is

$$

\begin{eqnarray}

F(t+\tau)=F(t).

\end{eqnarray}

$$

One example of a non-sinusoidal periodic force is a square wave. Many components in electric circuits are non-linear, for example diodes. This makes many wave forms non-sinusoidal even when the circuits are being driven by purely sinusoidal sources.

Simple Code Example

The code here shows a typical example of such a square wave generated using the functionality included in the scipy Python package. We have used a period of \( \tau=0.2 \).

import numpy as np

import math

from scipy import signal

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# number of points

n = 500

# start and final times

t0 = 0.0

tn = 1.0

# Period

t = np.linspace(t0, tn, n, endpoint=False)

SqrSignal = np.zeros(n)

SqrSignal = 1.0+signal.square(2*np.pi*5*t)

plt.plot(t, SqrSignal)

plt.ylim(-0.5, 2.5)

plt.show()

For the sinusoidal example the period is \( \tau=2\pi/\omega \). However, higher harmonics can also satisfy the periodicity requirement. In general, any force that satisfies the periodicity requirement can be expressed as a sum over harmonics,

$$

\begin{equation}

F(t)=\frac{f_0}{2}+\sum_{n>0} f_n\cos(2n\pi t/\tau)+g_n\sin(2n\pi t/\tau).

\tag{2}

\end{equation}

$$

Wrapping up Fourier transforms

We can write down the answer for \( x_{pn}(t) \), by substituting \( f_n/m \) or \( g_n/m \) for \( F_0/m \). By writing each factor \( 2n\pi t/\tau \) as \( n\omega t \), with \( \omega\equiv 2\pi/\tau \),

$$

\begin{equation}

\tag{3}

F(t)=\frac{f_0}{2}+\sum_{n>0}f_n\cos(n\omega t)+g_n\sin(n\omega t).

\end{equation}

$$

The solutions for \( x(t) \) then come from replacing \( \omega \) with \( n\omega \) for each term in the particular solution,

$$

\begin{eqnarray}

x_p(t)&=&\frac{f_0}{2k}+\sum_{n>0} \alpha_n\cos(n\omega t-\delta_n)+\beta_n\sin(n\omega t-\delta_n),\\

\nonumber

\alpha_n&=&\frac{f_n/m}{\sqrt{((n\omega)^2-\omega_0^2)+4\beta^2n^2\omega^2}},\\

\nonumber

\beta_n&=&\frac{g_n/m}{\sqrt{((n\omega)^2-\omega_0^2)+4\beta^2n^2\omega^2}},\\

\nonumber

\delta_n&=&\tan^{-1}\left(\frac{2\beta n\omega}{\omega_0^2-n^2\omega^2}\right).

\end{eqnarray}

$$

Finding the Coefficients

Because the forces have been applied for a long time, any non-zero damping eliminates the homogenous parts of the solution. We need then only consider the particular solution for each \( n \).

The problem is considered solved if one can find expressions for the coefficients \( f_n \) and \( g_n \), even though the solutions are expressed as an infinite sum. The coefficients can be extracted from the function \( F(t) \) by

$$

\begin{eqnarray}

\tag{4}

f_n&=&\frac{2}{\tau}\int_{-\tau/2}^{\tau/2} dt~F(t)\cos(2n\pi t/\tau),\\

\nonumber

g_n&=&\frac{2}{\tau}\int_{-\tau/2}^{\tau/2} dt~F(t)\sin(2n\pi t/\tau).

\end{eqnarray}

$$

To check the consistency of these expressions and to verify Eq. (4), one can insert the expansion of \( F(t) \) in Eq. (3) into the expression for the coefficients in Eq. (4) and see whether

$$

f_n=\frac{2}{\tau}\int_{-\tau/2}^{\tau/2} dt~\left\{\frac{f_0}{2}+\sum_{m>0}f_m\cos(m\omega t)+g_m\sin(m\omega t)\right\}\cos(n\omega t).

$$

Immediately, one can throw away all the terms with \( g_m \) because they convolute an even and an odd function. The term with \( f_0/2 \) disappears because \( \cos(n\omega t) \) is equally positive and negative over the interval and will integrate to zero. For all the terms \( f_m\cos(m\omega t) \) appearing in the sum, one can use angle addition formulas to see that \( \cos(m\omega t)\cos(n\omega t)=(1/2)(\cos[(m+n)\omega t]+\cos[(m-n)\omega t] \). This will integrate to zero unless \( m=n \). In that case the \( m=n \) term gives

$$

\begin{equation}

\int_{-\tau/2}^{\tau/2}dt~\cos^2(m\omega t)=\frac{\tau}{2},

\tag{5}

\end{equation}

$$

and

$$

f_n=\frac{2}{\tau}\int_{-\tau/2}^{\tau/2} dt~f_n/2=f_n.

$$

The same method can be used to check for the consistency of \( g_n \).

Final words on Fourier Transforms

The code here uses the Fourier series applied to a square wave signal. The code here visualizes the various approximations given by Fourier series compared with a square wave with period \( T=0.2 \) (dimensionless time), width \( 0.1 \) and max value of the force \( F=2 \). We see that when we increase the number of components in the Fourier series, the Fourier series approximation gets closer and closer to the square wave signal.

import numpy as np

import math

from scipy import signal

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# number of points

n = 500

# start and final times

t0 = 0.0

tn = 1.0

# Period

T =0.2

# Max value of square signal

Fmax= 2.0

# Width of signal

Width = 0.1

t = np.linspace(t0, tn, n, endpoint=False)

SqrSignal = np.zeros(n)

FourierSeriesSignal = np.zeros(n)

SqrSignal = 1.0+signal.square(2*np.pi*5*t+np.pi*Width/T)

a0 = Fmax*Width/T

FourierSeriesSignal = a0

Factor = 2.0*Fmax/np.pi

for i in range(1,500):

FourierSeriesSignal += Factor/(i)*np.sin(np.pi*i*Width/T)*np.cos(i*t*2*np.pi/T)

plt.plot(t, SqrSignal)

plt.plot(t, FourierSeriesSignal)

plt.ylim(-0.5, 2.5)

plt.show()

Fourier transforms and convolution

We can use Fourier transforms in our studies of convolution as well. To see this, assume we have two functions \( f \) and \( g \) and their corresponding Fourier transforms \( \hat{f} \) and \( \hat{g} \). We remind the reader that the Fourier transform reads (say for the function \( f \))

$$

\hat{f}(y)=\boldsymbol{F}[f(y)]=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} d\omega \exp{-i\omega y} f(\omega),

$$

and similarly we have

$$

\hat{g}(y)=\boldsymbol{F}[g(y)]=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} d\omega \exp{-i\omega y} g(\omega).

$$

The inverse Fourier transform is given by

$$

\boldsymbol{F}^{-1}[g(y)]=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} d\omega \exp{i\omega y} g(\omega).

$$

The inverse Fourier transform of the product of the two functions \( \hat{f}\hat{g} \) can be written as

$$

\boldsymbol{F}^{-1}[(\hat{f}\hat{g})(x)]=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} d\omega \exp{i\omega x} \hat{f}(\omega)\hat{g}(\omega).

$$

We can rewrite the latter as

$$

\boldsymbol{F}^{-1}[(\hat{f}\hat{g})(x)]=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} d\omega \exp{i\omega x} \hat{f}(\omega)\left[\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}g(y)dy \exp{-i\omega y}\right]=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}dy g(y)\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} d\omega \hat{f}(\omega) \exp{i\omega(x- y)},

$$

which is simply

$$

\boldsymbol{F}^{-1}[(\hat{f}\hat{g})(x)]=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}dy g(y)f(x-y)=(f*g)(x),

$$

the convolution of the functions \( f \) and \( g \).

Two-dimensional Objects

We are now ready to start studying the discrete convolutions relevant for convolutional neural networks. We often use convolutions over more than one dimension at a time. If we have a two-dimensional image \( I \) as input, we can have a filter defined by a two-dimensional kernel \( K \). This leads to an output \( S \)

$$

S_(i,j)=(I * K)(i,j) = \sum_m\sum_n I(m,n)K(i-m,j-n).

$$

Convolution is a commutatitave process, which means we can rewrite this equation as

$$

S_(i,j)=(I * K)(i,j) = \sum_m\sum_n I(i-m,j-n)K(m,n).

$$

Normally the latter is more straightforward to implement in a machine larning library since there is less variation in the range of values of \( m \) and \( n \).

Many deep learning libraries implement cross-correlation instead of convolution (although it is referred to s convolution)

$$

S_(i,j)=(I * K)(i,j) = \sum_m\sum_n I(i+m,j+n)K(m,n).

$$

More on Dimensionalities

In fields like signal processing (and imaging as well), one designs so-called filters. These filters are defined by the convolutions and are often hand-crafted. One may specify filters for smoothing, edge detection, frequency reshaping, and similar operations. However with neural networks the idea is to automatically learn the filters and use many of them in conjunction with non-linear operations (activation functions).

As an example consider a neural network operating on sound sequence data. Assume that we an input vector \( \boldsymbol{x} \) of length \( d=10^6 \). We construct then a neural network with onle hidden layer only with \( 10^4 \) nodes. This means that we will have a weight matrix with \( 10^4\times 10^6=10^{10} \) weights to be determined, together with \( 10^4 \) biases.

Assume furthermore that we have an output layer which is meant to train whether the sound sequence represents a human voice (true) or something else (false). It means that we have only one output node. But since this output node connects to \( 10^4 \) nodes in the hidden layer, there are in total \( 10^4 \) weights to be determined for the output layer, plus one bias. In total we have

$$

\mathrm{NumberParameters}=10^{10}+10^4+10^4+1 \approx 10^{10},

$$

that is ten billion parameters to determine.

Further Dimensionality Remarks

In today’s architecture one can train such neural networks, however this is a huge number of parameters for the task at hand. In general, it is a very wasteful and inefficient use of dense matrices as parameters. Just as importantly, such trained network parameters are very specific for the type of input data on which they were trained and the network is not likely to generalize easily to variations in the input.

The main principles that justify convolutions is locality of information and repetion of patterns within the signal. Sound samples of the input in adjacent spots are much more likely to affect each other than those that are very far away. Similarly, sounds are repeated in multiple times in the signal. While slightly simplistic, reasoning about such a sound example demonstrates this. The same principles then apply to images and other similar data.

CNNs in more detail

Let assume we have an input matrix \( I \) of dimensionality \( 3\times 3 \) and a \( 2\times 2 \) filter \( W \) given by the following matrices

$$

\boldsymbol{I}=\begin{bmatrix}i_{00} & i_{01} & i_{02} \\

i_{10} & i_{11} & i_{12} \\

i_{20} & i_{21} & i_{22} \end{bmatrix},

$$

and

$$

\boldsymbol{W}=\begin{bmatrix}w_{00} & w_{01} \\

w_{10} & w_{11}\end{bmatrix}.

$$

We introduce now the hyperparameter \( S \) stride. Stride represents how the filter \( W \) moves the convolution process on the matrix \( I \). We strongly recommend the repository on Arithmetic of deep learning by Dumoulin and Visin

Here we set the stride equal to \( S=1 \), which means that, starting with the element \( i_{00} \), the filter will act on \( 2\times 2 \) submatrices each time, starting with the upper corner and moving according to the stride value column by column.

Here we perform the operation

$$

S_(i,j)=(I * W)(i,j) = \sum_m\sum_n I(i-m,j-n)W(m,n),

$$

and obtain

$$

\boldsymbol{S}=\begin{bmatrix}i_{00}w_{00}+i_{01}w_{01}+i_{10}w_{10}+i_{11}w_{11} & i_{01}w_{00}+i_{02}w_{01}+i_{11}w_{10}+i_{12}w_{11} \\

i_{10}w_{00}+i_{11}w_{01}+i_{20}w_{10}+i_{21}w_{11} & i_{11}w_{00}+i_{12}w_{01}+i_{21}w_{10}+i_{22}w_{11}\end{bmatrix}.

$$

We can rewrite this operation in terms of a matrix-vector multiplication by defining a new vector where we flatten out the inputs as a vector \( \boldsymbol{I}' \) of length \( 9 \) and a matrix \( \boldsymbol{W}' \) with dimension \( 4\times 9 \) as

$$

\boldsymbol{I}'=\begin{bmatrix}i_{00} \\ i_{01} \\ i_{02} \\ i_{10} \\ i_{11} \\ i_{12} \\ i_{20} \\ i_{21} \\ i_{22} \end{bmatrix},

$$

and the new matrix

$$

\boldsymbol{W}'=\begin{bmatrix} w_{00} & w_{01} & 0 & w_{10} & w_{11} & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & w_{00} & w_{01} & 0 & w_{10} & w_{11} & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & w_{00} & w_{01} & 0 & w_{10} & w_{11} & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & w_{00} & w_{01} & 0 & w_{10} & w_{11}\end{bmatrix}.

$$

We see easily that performing the matrix-vector multiplication \( \boldsymbol{W}'\boldsymbol{I}' \) is the same as the above convolution with stride \( S=1 \), that is

$$

S=(\boldsymbol{W}*\boldsymbol{I}),

$$

is now given by \( \boldsymbol{W}'\boldsymbol{I}' \) which is a vector of length \( 4 \) instead of the originally resulting \( 2\times 2 \) output matrix.

The collection of kernels/filters \( W \) defining a discrete convolution has a shape corresponding to some permutation of \( (n, m, k_1, \ldots, k_N) \), where

$$ \begin{equation*} \begin{split} n &\equiv \text{number of output feature maps},\\ m &\equiv \text{number of input feature maps},\\ k_j &\equiv \text{kernel size along axis $j$}. \end{split} \end{equation*} $$The following properties affect the output size \( o_j \) of a convolutional layer along axis \( j \):

- \( i_j \): input size along axis \( j \),

- \( k_j \): kernel/filter size along axis \( j \),

- stride (distance between two consecutive positions of the kernel/filter) along axis \( j \),

- zero padding (number of zeros concatenated at the beginning and at the end of an axis) along axis \( j \).

For instance, the above examples shows a \( 2\times 2 \) kernel/filter \( \boldsymbol{W} \) applied to a \( 3 \times 3 \) input padded with a \( 0 \times 0 \) border of zeros using \( 1 \times 1 \) strides.

Note that strides constitute a form of subsampling. As an alternative to being interpreted as a measure of how much the kernel/filter is translated, strides can also be viewed as how much of the output is retained. For instance, moving the kernel by hops of two is equivalent to moving the kernel by hops of one but retaining only odd output elements.

Pooling

In addition to discrete convolutions themselves, pooling operations make up another important building block in CNNs. Pooling operations reduce the size of feature maps by using some function to summarize subregions, such as taking the average or the maximum value.

Pooling works by sliding a window across the input and feeding the content of the window to a pooling function. In some sense, pooling works very much like a discrete convolution, but replaces the linear combination described by the kernel with some other function. Pooling provides an example for average pooling, and does the same for max pooling.

The following properties affect the output size \( o_j \) of a pooling layer along axis \( j \):

- \( i_j \): input size along axis \( j \),

- \( k_j \): pooling window size along axis \( j \),

- \( s_j \): stride (distance between two consecutive positions of the pooling window) along axis \( j \).

The analysis of the relationship between convolutional layer properties is eased by the fact that they don't interact across axes, i.e., the choice of kernel size, stride and zero padding along axis \( j \) only affects the output size of axis \( j \). Because of that, we will focus on the following simplified setting:

- 2-D discrete convolutions (\( N = 2 \)),

- square inputs (\( i_1 = i_2 = i \)),

- square kernel size (\( k_1 = k_2 = k \)),

- same strides along both axes (\( s_1 = s_2 = s \)),

- same zero padding along both axes (\( p_1 = p_2 = p \)).

This facilitates the analysis and the visualization, but keep in mind that the results outlined here also generalize to the N-D and non-square cases.

No zero padding, unit strides

The simplest case to analyze is when the kernel just slides across every position of the input (i.e., \( s = 1 \) and \( p = 0 \)).

For any \( i \) and \( k \), and for \( s = 1 \) and \( p = 0 \),

$$

\begin{equation*}

o = (i - k) + 1.

\end{equation*}

$$

Zero padding, unit strides

To factor in zero padding (i.e., only restricting to \( s = 1 \)), let's consider its effect on the effective input size: padding with \( p \) zeros changes the effective input size from \( i \) to \( i + 2p \). In the general case, we can infer the following relationship

For any \( i \), \( k \) and \( p \), and for \( s = 1 \),

$$

\begin{equation*}

o = (i - k) + 2p + 1.

\end{equation*}

$$

Half (same) padding

Having the output size be the same as the input size (i.e., \( o = i \)) can be a desirable property:

For any \( i \) and for \( k \) odd (\( k = 2n + 1, \quad n \in \mathbb{N} \)), \( s = 1 \) and \( p = \lfloor k / 2 \rfloor = n \),

$$

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

o &= i + 2 \lfloor k / 2 \rfloor - (k - 1) \\

&= i + 2n - 2n \\

&= i.

\end{split}

\end{equation*}

$$

Full padding

While convolving a kernel generally decreases the output size with respect to the input size, sometimes the opposite is required. This can be achieved with proper zero padding:

For any \( i \) and \( k \), and for \( p = k - 1 \) and \( s = 1 \),

$$

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

o &= i + 2(k - 1) - (k - 1) \\

&= i + (k - 1).

\end{split}

\end{equation*}

$$

This is sometimes referred to as full padding, because in this setting every possible partial or complete superimposition of the kernel on the input feature map is taken into account.

Pooling arithmetic

In a neural network, pooling layers provide invariance to small translations of the input. The most common kind of pooling is max pooling, which consists in splitting the input in (usually non-overlapping) patches and outputting the maximum value of each patch. Other kinds of pooling exist, e.g., mean or average pooling, which all share the same idea of aggregating the input locally by applying a non-linearity to the content of some patches.

Since pooling does not involve zero padding, the relationship describing the general case is as follows:

For any \( i \), \( k \) and \( s \),

$$

\begin{equation*}

o = \left\lfloor \frac{i - k}{s} \right\rfloor + 1.

\end{equation*}

$$

CNNs in more detail, building convolutional neural networks in Tensorflow and Keras

As discussed above, CNNs are neural networks built from the assumption that the inputs to the network are 2D images. This is important because the number of features or pixels in images grows very fast with the image size, and an enormous number of weights and biases are needed in order to build an accurate network.

As before, we still have our input, a hidden layer and an output. What's novel about convolutional networks are the convolutional and pooling layers stacked in pairs between the input and the hidden layer. In addition, the data is no longer represented as a 2D feature matrix, instead each input is a number of 2D matrices, typically 1 for each color dimension (Red, Green, Blue).

Setting it up

It means that to represent the entire dataset of images, we require a 4D matrix or tensor. This tensor has the dimensions:

$$

(n_{inputs},\, n_{pixels, width},\, n_{pixels, height},\, depth) .

$$

The MNIST dataset again

The MNIST dataset consists of grayscale images with a pixel size of \( 28\times 28 \), meaning we require \( 28 \times 28 = 724 \) weights to each neuron in the first hidden layer.

If we were to analyze images of size \( 128\times 128 \) we would require \( 128 \times 128 = 16384 \) weights to each neuron. Even worse if we were dealing with color images, as most images are, we have an image matrix of size \( 128\times 128 \) for each color dimension (Red, Green, Blue), meaning 3 times the number of weights \( = 49152 \) are required for every single neuron in the first hidden layer.

Strong correlations

Images typically have strong local correlations, meaning that a small part of the image varies little from its neighboring regions. If for example we have an image of a blue car, we can roughly assume that a small blue part of the image is surrounded by other blue regions.

Therefore, instead of connecting every single pixel to a neuron in the first hidden layer, as we have previously done with deep neural networks, we can instead connect each neuron to a small part of the image (in all 3 RGB depth dimensions). The size of each small area is fixed, and known as a receptive.

Layers of a CNN

The layers of a convolutional neural network arrange neurons in 3D: width, height and depth. The input image is typically a square matrix of depth 3.

A convolution is performed on the image which outputs a 3D volume of neurons. The weights to the input are arranged in a number of 2D matrices, known as filters.

Each filter slides along the input image, taking the dot product between each small part of the image and the filter, in all depth dimensions. This is then passed through a non-linear function, typically the Rectified Linear (ReLu) function, which serves as the activation of the neurons in the first convolutional layer. This is further passed through a pooling layer, which reduces the size of the convolutional layer, e.g. by taking the maximum or average across some small regions, and this serves as input to the next convolutional layer.

Systematic reduction

By systematically reducing the size of the input volume, through convolution and pooling, the network should create representations of small parts of the input, and then from them assemble representations of larger areas. The final pooling layer is flattened to serve as input to a hidden layer, such that each neuron in the final pooling layer is connected to every single neuron in the hidden layer. This then serves as input to the output layer, e.g. a softmax output for classification.

Prerequisites: Collect and pre-process data

# import necessary packages

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn import datasets

# ensure the same random numbers appear every time

np.random.seed(0)

# display images in notebook

%matplotlib inline

plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (12,12)

# download MNIST dataset

digits = datasets.load_digits()

# define inputs and labels

inputs = digits.images

labels = digits.target

# RGB images have a depth of 3

# our images are grayscale so they should have a depth of 1

inputs = inputs[:,:,:,np.newaxis]

print("inputs = (n_inputs, pixel_width, pixel_height, depth) = " + str(inputs.shape))

print("labels = (n_inputs) = " + str(labels.shape))

# choose some random images to display

n_inputs = len(inputs)

indices = np.arange(n_inputs)

random_indices = np.random.choice(indices, size=5)

for i, image in enumerate(digits.images[random_indices]):

plt.subplot(1, 5, i+1)

plt.axis('off')

plt.imshow(image, cmap=plt.cm.gray_r, interpolation='nearest')

plt.title("Label: %d" % digits.target[random_indices[i]])

plt.show()

Importing Keras and Tensorflow

from tensorflow.keras import datasets, layers, models

from tensorflow.keras.layers import Input

from tensorflow.keras.models import Sequential #This allows appending layers to existing models

from tensorflow.keras.layers import Dense #This allows defining the characteristics of a particular layer

from tensorflow.keras import optimizers #This allows using whichever optimiser we want (sgd,adam,RMSprop)

from tensorflow.keras import regularizers #This allows using whichever regularizer we want (l1,l2,l1_l2)

from tensorflow.keras.utils import to_categorical #This allows using categorical cross entropy as the cost function

#from tensorflow.keras import Conv2D

#from tensorflow.keras import MaxPooling2D

#from tensorflow.keras import Flatten

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# representation of labels

labels = to_categorical(labels)

# split into train and test data

# one-liner from scikit-learn library

train_size = 0.8

test_size = 1 - train_size

X_train, X_test, Y_train, Y_test = train_test_split(inputs, labels, train_size=train_size,

test_size=test_size)

Running with Keras

def create_convolutional_neural_network_keras(input_shape, receptive_field,

n_filters, n_neurons_connected, n_categories,

eta, lmbd):

model = Sequential()

model.add(layers.Conv2D(n_filters, (receptive_field, receptive_field), input_shape=input_shape, padding='same',

activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(lmbd)))

model.add(layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2)))

model.add(layers.Flatten())

model.add(layers.Dense(n_neurons_connected, activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(lmbd)))

model.add(layers.Dense(n_categories, activation='softmax', kernel_regularizer=regularizers.l2(lmbd)))

sgd = optimizers.SGD(lr=eta)

model.compile(loss='categorical_crossentropy', optimizer=sgd, metrics=['accuracy'])

return model

epochs = 100

batch_size = 100

input_shape = X_train.shape[1:4]

receptive_field = 3

n_filters = 10

n_neurons_connected = 50

n_categories = 10

eta_vals = np.logspace(-5, 1, 7)

lmbd_vals = np.logspace(-5, 1, 7)

Final part

CNN_keras = np.zeros((len(eta_vals), len(lmbd_vals)), dtype=object)

for i, eta in enumerate(eta_vals):

for j, lmbd in enumerate(lmbd_vals):

CNN = create_convolutional_neural_network_keras(input_shape, receptive_field,

n_filters, n_neurons_connected, n_categories,

eta, lmbd)

CNN.fit(X_train, Y_train, epochs=epochs, batch_size=batch_size, verbose=0)

scores = CNN.evaluate(X_test, Y_test)

CNN_keras[i][j] = CNN

print("Learning rate = ", eta)

print("Lambda = ", lmbd)

print("Test accuracy: %.3f" % scores[1])

print()

Final visualization

# visual representation of grid search

# uses seaborn heatmap, could probably do this in matplotlib

import seaborn as sns

sns.set()

train_accuracy = np.zeros((len(eta_vals), len(lmbd_vals)))

test_accuracy = np.zeros((len(eta_vals), len(lmbd_vals)))

for i in range(len(eta_vals)):

for j in range(len(lmbd_vals)):

CNN = CNN_keras[i][j]

train_accuracy[i][j] = CNN.evaluate(X_train, Y_train)[1]

test_accuracy[i][j] = CNN.evaluate(X_test, Y_test)[1]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (10, 10))

sns.heatmap(train_accuracy, annot=True, ax=ax, cmap="viridis")

ax.set_title("Training Accuracy")

ax.set_ylabel("$\eta$")

ax.set_xlabel("$\lambda$")

plt.show()

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize = (10, 10))

sns.heatmap(test_accuracy, annot=True, ax=ax, cmap="viridis")

ax.set_title("Test Accuracy")

ax.set_ylabel("$\eta$")

ax.set_xlabel("$\lambda$")

plt.show()

The CIFAR01 data set

The CIFAR10 dataset contains 60,000 color images in 10 classes, with 6,000 images in each class. The dataset is divided into 50,000 training images and 10,000 testing images. The classes are mutually exclusive and there is no overlap between them.

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow.keras import datasets, layers, models

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# We import the data set

(train_images, train_labels), (test_images, test_labels) = datasets.cifar10.load_data()

# Normalize pixel values to be between 0 and 1 by dividing by 255.

train_images, test_images = train_images / 255.0, test_images / 255.0

Verifying the data set

To verify that the dataset looks correct, let's plot the first 25 images from the training set and display the class name below each image.

class_names = ['airplane', 'automobile', 'bird', 'cat', 'deer',

'dog', 'frog', 'horse', 'ship', 'truck']

plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

for i in range(25):

plt.subplot(5,5,i+1)

plt.xticks([])

plt.yticks([])

plt.grid(False)

plt.imshow(train_images[i], cmap=plt.cm.binary)

# The CIFAR labels happen to be arrays,

# which is why you need the extra index

plt.xlabel(class_names[train_labels[i][0]])

plt.show()

Set up the model

The 6 lines of code below define the convolutional base using a common pattern: a stack of Conv2D and MaxPooling2D layers.

As input, a CNN takes tensors of shape (image_height, image_width, color_channels), ignoring the batch size. If you are new to these dimensions, color_channels refers to (R,G,B). In this example, you will configure our CNN to process inputs of shape (32, 32, 3), which is the format of CIFAR images. You can do this by passing the argument input_shape to our first layer.

model = models.Sequential()

model.add(layers.Conv2D(32, (3, 3), activation='relu', input_shape=(32, 32, 3)))

model.add(layers.MaxPooling2D((2, 2)))

model.add(layers.Conv2D(64, (3, 3), activation='relu'))

model.add(layers.MaxPooling2D((2, 2)))

model.add(layers.Conv2D(64, (3, 3), activation='relu'))

# Let's display the architecture of our model so far.

model.summary()

You can see that the output of every Conv2D and MaxPooling2D layer is a 3D tensor of shape (height, width, channels). The width and height dimensions tend to shrink as you go deeper in the network. The number of output channels for each Conv2D layer is controlled by the first argument (e.g., 32 or 64). Typically, as the width and height shrink, you can afford (computationally) to add more output channels in each Conv2D layer.

Add Dense layers on top

To complete our model, you will feed the last output tensor from the convolutional base (of shape (4, 4, 64)) into one or more Dense layers to perform classification. Dense layers take vectors as input (which are 1D), while the current output is a 3D tensor. First, you will flatten (or unroll) the 3D output to 1D, then add one or more Dense layers on top. CIFAR has 10 output classes, so you use a final Dense layer with 10 outputs and a softmax activation.

model.add(layers.Flatten())

model.add(layers.Dense(64, activation='relu'))

model.add(layers.Dense(10))

Here's the complete architecture of our model.

model.summary()

As you can see, our (4, 4, 64) outputs were flattened into vectors of shape (1024) before going through two Dense layers.

Compile and train the model

model.compile(optimizer='adam',

loss=tf.keras.losses.SparseCategoricalCrossentropy(from_logits=True),

metrics=['accuracy'])

history = model.fit(train_images, train_labels, epochs=10,

validation_data=(test_images, test_labels))

Finally, evaluate the model

plt.plot(history.history['accuracy'], label='accuracy')

plt.plot(history.history['val_accuracy'], label = 'val_accuracy')

plt.xlabel('Epoch')

plt.ylabel('Accuracy')

plt.ylim([0.5, 1])

plt.legend(loc='lower right')

test_loss, test_acc = model.evaluate(test_images, test_labels, verbose=2)

print(test_acc)

Building our own CNN code

Here we present a flexible and readable python code for a CNN implemented with NumPy. We will present the code, showcase how to use the codebase and fit a CNN that yields a 99% accuracy on the 28x28 MNIST dataset within reasonable time.

The CNN is compatible with all schedulers, cost functions and activation functions discussed in constructing our neural network codes.

The CNN code consists of different types of Layer classes, including Convolution2DLayer, Pooling2DLayer, FlattenLayer, FullyConnectedLayer and OutputLayer, which can be added to the CNN object using the interface of the CNN class. This allows you to easily construct your own CNN, as well as allowing you to get used to an interface similar to that of TensorFlow which is used for real world applications.

Another important feature of this code is that it throws errors if unreasonable decisions are made (for example using a kernel that is larger than the image, not using a FlattenLayer, etc), and provides the user with an informative error message.

List of contents:

- Schedulers

- Activation Functions

- Cost Functions

- Convolution

- Layers

- CNN

- Some final remarks

Schedulers

The code below shows object oriented implementations of the Constant, Momentum, Adagrad, AdagradMomentum, RMS prop and Adam schedulers. All of the classes belong to the shared abstract Scheduler class, and share the update_change() and reset() methods allowing for any of the schedulers to be seamlessly used during the training stage, as will later be shown in the fit() method of the neural network. Update_change() only has one parameter, the gradient (\( \delta^{l}_{j}a^{l-1}_k \)), and returns the change which will be subtracted from the weights. The reset() function takes no parameters, and resets the desired variables. For Constant and Momentum, reset does nothing.

import autograd.numpy as np

class Scheduler:

"""

Abstract class for Schedulers

"""

def __init__(self, eta):

self.eta = eta

# should be overwritten

def update_change(self, gradient):

raise NotImplementedError

# overwritten if needed

def reset(self):

pass

class Constant(Scheduler):

def __init__(self, eta):

super().__init__(eta)

def update_change(self, gradient):

return self.eta * gradient

def reset(self):

pass

class Momentum(Scheduler):

def __init__(self, eta: float, momentum: float):

super().__init__(eta)

self.momentum = momentum

self.change = 0

def update_change(self, gradient):

self.change = self.momentum * self.change + self.eta * gradient

return self.change

def reset(self):

pass

class Adagrad(Scheduler):

def __init__(self, eta):

super().__init__(eta)

self.G_t = None

def update_change(self, gradient):

delta = 1e-8 # avoid division ny zero

if self.G_t is None:

self.G_t = np.zeros((gradient.shape[0], gradient.shape[0]))

self.G_t += gradient @ gradient.T

G_t_inverse = 1 / (

delta + np.sqrt(np.reshape(np.diagonal(self.G_t), (self.G_t.shape[0], 1)))

)

return self.eta * gradient * G_t_inverse

def reset(self):

self.G_t = None

class AdagradMomentum(Scheduler):

def __init__(self, eta, momentum):

super().__init__(eta)

self.G_t = None

self.momentum = momentum

self.change = 0

def update_change(self, gradient):

delta = 1e-8 # avoid division ny zero

if self.G_t is None:

self.G_t = np.zeros((gradient.shape[0], gradient.shape[0]))

self.G_t += gradient @ gradient.T

G_t_inverse = 1 / (

delta + np.sqrt(np.reshape(np.diagonal(self.G_t), (self.G_t.shape[0], 1)))

)

self.change = self.change * self.momentum + self.eta * gradient * G_t_inverse

return self.change

def reset(self):

self.G_t = None

class RMS_prop(Scheduler):

def __init__(self, eta, rho):

super().__init__(eta)

self.rho = rho

self.second = 0.0

def update_change(self, gradient):

delta = 1e-8 # avoid division ny zero

self.second = self.rho * self.second + (1 - self.rho) * gradient * gradient

return self.eta * gradient / (np.sqrt(self.second + delta))

def reset(self):

self.second = 0.0

class Adam(Scheduler):

def __init__(self, eta, rho, rho2):

super().__init__(eta)

self.rho = rho

self.rho2 = rho2

self.moment = 0

self.second = 0

self.n_epochs = 1

def update_change(self, gradient):

delta = 1e-8 # avoid division ny zero

self.moment = self.rho * self.moment + (1 - self.rho) * gradient

self.second = self.rho2 * self.second + (1 - self.rho2) * gradient * gradient

moment_corrected = self.moment / (1 - self.rho**self.n_epochs)

second_corrected = self.second / (1 - self.rho2**self.n_epochs)

return self.eta * moment_corrected / (np.sqrt(second_corrected + delta))

def reset(self):

self.n_epochs += 1

self.moment = 0

self.second = 0

Usage of schedulers

To initalize a scheduler, simply create the object and pass in the necessary parameters such as the learning rate and the momentum as shown below. As the Scheduler class is an abstract class it should not called directly, and will raise an error upon usage.

momentum_scheduler = Momentum(eta=1e-3, momentum=0.9)

adam_scheduler = Adam(eta=1e-3, rho=0.9, rho2=0.999)

Here is a small example for how a segment of code using schedulers could look. Switching out the schedulers is simple.

weights = np.ones((3,3))

print(f"Before scheduler:\n{weights=}")

epochs = 10

for e in range(epochs):

gradient = np.random.rand(3, 3)

change = adam_scheduler.update_change(gradient)

weights = weights - change

adam_scheduler.reset()

print(f"\nAfter scheduler:\n{weights=}")

Cost functions

In this section we will quickly look at cost functions that can be used when creating the neural network. Every cost function takes the target vector as its parameter, and returns a function valued only at X such that it may easily be differentiated.

def CostOLS(target):

"""

Return OLS function valued only at X, so

that it may be easily differentiated

"""

def func(X):

return (1.0 / target.shape[0]) * np.sum((target - X) ** 2)

return func

def CostLogReg(target):

"""

Return Logistic Regression cost function

valued only at X, so that it may be easily differentiated

"""

def func(X):

return -(1.0 / target.shape[0]) * np.sum(

(target * np.log(X + 10e-10)) + ((1 - target) * np.log(1 - X + 10e-10))

)

return func

def CostCrossEntropy(target):

"""

Return cross entropy cost function valued only at X, so

that it may be easily differentiated

"""

def func(X):

return -(1.0 / target.size) * np.sum(target * np.log(X + 10e-10))

return func

Usage of cost functions

Below we will provide a short example of how these cost function may be used to obtain results if you wish to test them out on your own using AutoGrad's automatic differentiation.

from autograd import grad

target = np.array([[1, 2, 3]]).T

a = np.array([[4, 5, 6]]).T

cost_func = CostCrossEntropy

cost_func_derivative = grad(cost_func(target))

valued_at_a = cost_func_derivative(a)

print(f"Derivative of cost function {cost_func.__name__} valued at a:\n{valued_at_a}")

Activation functions

Finally, before we look at the layers that make up the neural network, we will look at the activation functions which can be specified between the hidden layers and as the output function. Each function can be valued for any given vector or matrix X, and can be differentiated via derivate().

import autograd.numpy as np

from autograd import elementwise_grad

def identity(X):

return X

def sigmoid(X):

try:

return 1.0 / (1 + np.exp(-X))

except FloatingPointError:

return np.where(X > np.zeros(X.shape), np.ones(X.shape), np.zeros(X.shape))

def softmax(X):

X = X - np.max(X, axis=-1, keepdims=True)

delta = 10e-10

return np.exp(X) / (np.sum(np.exp(X), axis=-1, keepdims=True) + delta)

def RELU(X):

return np.where(X > np.zeros(X.shape), X, np.zeros(X.shape))

def LRELU(X):

delta = 10e-4

return np.where(X > np.zeros(X.shape), X, delta * X)

def derivate(func):

if func.__name__ == "RELU":

def func(X):

return np.where(X > 0, 1, 0)

return func

elif func.__name__ == "LRELU":

def func(X):

delta = 10e-4

return np.where(X > 0, 1, delta)

return func

else:

return elementwise_grad(func)

Usage of activation functions

Below we present a short demonstration of how to use an activation function. The derivative of the activation function will be important when calculating the output delta term during backpropagation. Note that derivate() can also be used for cost functions for a more generalized approach.

z = np.array([[4, 5, 6]]).T

print(f"Input to activation function:\n{z}")

act_func = sigmoid

a = act_func(z)

print(f"\nOutput from {act_func.__name__} activation function:\n{a}")

act_func_derivative = derivate(act_func)

valued_at_z = act_func_derivative(a)

print(f"\nDerivative of {act_func.__name__} activation function valued at z:\n{valued_at_z}")

Convolution

In order to construct a convolutional neural network (CNN), it is crucial to comprehend the fundamental principles of convolution and how it aids in extracting information from images. Convolution, at its core, is merely a mathematical operation between two functions that yields another function. It is represented by an integral between two functions, which is typically expressed as:

$$

(f \ast g)(t):=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(\tau) g(t-\tau) d \tau.

$$

Here, f and g are the two functions on which we want to perform an operation. The outcome of the convolution operation is represented by \( (f \ast g) \), and it is derived by sliding the function g over f and computing the integral of their product at each position. If both functions are continuous, convolution takes the form shown above. However, if we discretize both f and g, the convolution operation will take the form of a sum between the elements of f and g:

$$

(f \ast g)[n]=\sum_{m=0}^{n-1} f[m] g[n-m].

$$

The key idea we utilize to extract the information contained in an image is to slide an \( m \times n \) matrix g over an \( m \times n \) matrix f. In our case, f represents the image, while g represents the kernel, oftentimes called a filter. However, since our convolution will be a two-dimensional variant, we need to extend our mathematical formula with an additional summation:

$$

(f \ast g)[i, j]\sum_{m=0}^{M-1}\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} f[m,n] g[i-m, j-n].

$$

It is imperative to note that the size of the kernel g is significantly smaller than the size of the input image f, thereby reducing the amount of computation necessary for feature extraction. Furthermore, the kernel is usually a trainable parameter in a convolutional neural network, allowing the network to learn appropriate kernels for specific tasks.

To give you an example of how 2D convolution works in practice, suppose we have an image f of dimension \( 6 \times 6 \)

$$

f = \begin{bmatrix}

4 & 1 & 2 & 9 & 8 & 6 \\

9 & 5 & 9 & 5 & 8 & 5 \\

1 & 5 & 9 & 7 & 6 & 4 \\

2 & 9 & 8 & 3 & 7 & 1 \\

8 & 1 & 6 & 4 & 2 & 2 \\

1 & 0 & 5 & 7 & 8 & 2 \\

\end{bmatrix}

$$

and a \( 3 \times 3 \) kernel g called a low-pass filter. Note that the kernel is usually rotated by 180 degrees during convolution, however this has no effect on this kernel.

$$

g = \frac{1}{9}

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 1 & 1 \\

1 & 1 & 1 \\

1 & 1 & 1 \\

\end{bmatrix}

$$

In order to filter the image, we have to extract a \( 3 \times 3 \) element from the upper left corner of f, and perform element-wise multiplication of the extracted image pixels with the elements of the kernel g:

$$

\begin{bmatrix}

4 & 1 & 2 \\

9 & 5 & 9 \\

1 & 5 & 9 \\

\end{bmatrix}

\cdot

\begin{bmatrix}

\frac{1}{9} & \frac{1}{9} & \frac{1}{9} \\

\frac{1}{9} & \frac{1}{9} & \frac{1}{9} \\

\frac{1}{9} & \frac{1}{9} & \frac{1}{9} \\

\end{bmatrix}

=

\begin{bmatrix}

\frac{4}{9} & \frac{1}{9} & \frac{2}{9} \\

\frac{9}{9} & \frac{5}{9} & \frac{9}{9} \\

\frac{1}{9} & \frac{5}{9} & \frac{9}{9} \\

\end {bmatrix}

= \textbf{A}

$$

Then, following the multiplication, we summarize all the elements of the resulting matrix A:

$$

(f \ast g)[0, 0]= \sum_{i=0}^{2} \sum_{j=0}^{2} a_{i,j} = 5

$$

Which corresponds to the first element of the filtered image \( (f \ast g) \).

Here we use a stride of 1, a parameter denoted s which describes how many indexes we move the kernel g to the right before repeating the calculations above for the next \( 3 \times 3 \) element of the image f. It is usually presumed that *s*=1, however, larger values for s can be used to reduce the dimentionality of the filtered image such that the convolution operation is more computationally efficient. In the context of a convolutional neural network, this will become very useful.

The full result of the convolution is:

$$

(f \ast g) =

\begin{bmatrix}

5 & 5.78 & 7 & 6.44 \\

6.33 & 6.67 & 6.89 & 5.11 \\

5.44 & 5.78 & 5.78 & 4 \\

4.44 & 4.78 & 5.56 & 4 \\

\end{bmatrix}

$$

The result is markedly smaller in shape than the original image. This occurs when using convolution without first padding the image with additional columns and rows, allowing us to keep the original image shape after sliding the kernel over the image. How many rows and columns we wish to pad the image with depends strictly on the shape of the kernel, as we wish to pad the image with r additional rows and c additional columns.

$$

r =\lfloor \frac{kernel\ height}{2} \rfloor \cdot 2 \\

c =\lfloor \frac{kernel\ width}{2} \rfloor \cdot 2

$$

Note the notation \( \lfloor \frac{kernel width}{2} \rfloor \) means that we floor the result of the division, meaning we round down to a whole number in case \( \frac{kernel width}{2} \) results in a floating point number.

Using those simple equations, we find out by how much we have to extend the dimensions of the original image. Before proceeding, however, we might ask what we shall fill the additional rows and columns with? One of the most common approaches to padding is zero-padding, which as the name suggest, involves filling the rows and columns with zeros. This is the approach that we will be using for this demonstration. If we apply this padding to out original \( 6 \times 6 \) image, the result will be an \( 8 \times 8 \) image as the kernel has a width and height of 3. Note that the original image is encapsuled by the zero-padded rows and columns:

$$

\begin{bmatrix}

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 4 & 1 & 2 & 9 & 8 & 6 & 0 \\

0 & 9 & 5 & 9 & 5 & 8 & 5 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 5 & 9 & 7 & 6 & 4 & 0 \\

0 & 2 & 9 & 8 & 3 & 7 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 8 & 1 & 6 & 4 & 2 & 2 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 5 & 7 & 8 & 2 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

\]

\end{bmatrix}

$$

Below we have provided code that demonstrates padding and convolution. As you will see when we run the code, the size of the image will remain unchanged when using padding.

import numpy as np

def padding(image, kernel):

# calculate r and c

r = (kernel.shape[0] // 2) * 2

c = (kernel.shape[1] // 2) * 2

# padded image dimensions

padded_height = image.shape[0] + r

padded_width = image.shape[1] + c

# for more readable code

k_half_height = kernel.shape[0] // 2

k_half_width = kernel.shape[1] // 2

# zero matrix with padded dimensions

padded_img = np.zeros((padded_height, padded_width))

# place image into zero matrix

padded_img[k_half_height : padded_height - k_half_height,

k_half_width : padded_width - k_half_width] = image[:, :]

return padded_img

def convolve(original_image, padded_image, kernel, stride=1):

# rotate kernel by 180 degrees

kernel = np.rot90(np.rot90(kernel))

# note that kernel height // 2 is written as 'm'

# and kernel width // 2 as 'n' in the mathematical notation

m = kernel.shape[0] // 2

n = kernel.shape[1] // 2

r = (kernel.shape[0] // 2) * 2

c = (kernel.shape[1] // 2) * 2

# initialize output array

convolved_image = np.zeros(original_image.shape)

image_height = original_image.shape[0]

image_width = original_image.shape[1]

# the convolution

for i in range(m, image_height + m, stride):

for j in range(n, image_width + n, stride):

convolved_image[i-m, j-n] = np.sum(

padded_image[i : i + m, j : j + n]

* kernel

)

return convolved_image

def convolve(image, kernel, stride=1):

for i in range(2):

kernel = np.rot90(kernel)

k_half_height = kernel.shape[0] // 2

k_half_width = kernel.shape[0] // 2

conv_image = np.zeros(image.shape)

pad_image = padding(image, kernel)

for i in range(k_half_height, conv_image.shape[0] + k_half_height, stride):

for j in range(k_half_width, conv_image.shape[1] + k_half_width, stride):

conv_image[i - k_half_height, j - k_half_width] = np.sum(

pad_image[

i - k_half_height : i + k_half_height + 1, j - k_half_width : j + k_half_width + 1

]

* kernel

)

return conv_image

Fun fact: When filtering images, you will see that convolution involves rotating the kernel by 180 degrees. However, this is not the case when applying convolution in a CNN, where the same operation not rotated by 180 degrees is called cross-correlation.

original_image = np.array([[4, 1, 2, 9, 8, 6],

[9, 5, 9, 5, 8, 5],

[1, 5, 9, 7, 6, 4],

[2, 9, 8, 3, 7, 1],

[8, 1, 6, 4, 2, 2],

[1, 0, 5, 7, 8, 2]])

kernel = (1/9)*np.ones((3,3))

print(f"{original_image.shape=}")

# note that convolve() performs padding

convolved_image = convolve(original_image, kernel, stride=1)

print(f"{convolved_image.shape=}")

As you can see, the resulting image is of the same size as the original image. To round of our demonstration of convolution, we will present the results of convolution using commonly used kernels. In a CNN, the values of the kernels are randomly initialized, and then learned during training. These kernels will extract information regarding the picture, such as for example the edge detection filter demonstrated below extracts the edges present in the picture. Of course, there is no guarantee that the CNN will learn an edge detection filter, but this should provide some intuiton as to how the CNN is able to use kernels to make better predictions than a regular feed forward neural network.

# Now an example using a real image and first a gaussian low-pass filter and then a sobel filter

import numpy as np

import imageio.v3 as imageio

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import time

def generate_gauss_mask(sigma, K=1):

side = np.ceil(1 + 8 * sigma)

y, x = np.mgrid[-side // 2 + 1 : (side // 2) + 1, -side // 2 + 1 : (side // 2) + 1]

ker_coef = K / (2 * np.pi * sigma**2)

g = np.exp(-((x**2 + y**2) / (2.0 * sigma**2)))

return g, ker_coef

img_path = "data/IMG-2167.JPG"

image_of_cute_dog = imageio.imread(img_path, mode='L')

plt.imshow(image_of_cute_dog, cmap="gray", vmin=0, vmax=255, aspect="auto")

plt.title("Original image")

plt.show()

gauss, kernel = generate_gauss_mask(sigma=6)

gauss_kernel = gauss*kernel

filtered_image = convolve(image_of_cute_dog, gauss_kernel)

plt.imshow(filtered_image, cmap="gray", vmin=0, vmax=255, aspect="auto")

plt.title("Result of convolution with gauss kernel (blurring filter)")

plt.show()

sobel_kernel = np.array([[1, 2, 1],

[0, 0, 0],

[-1, -2, -1]])

filtered_image = convolve(image_of_cute_dog, sobel_kernel)

plt.imshow(filtered_image, cmap="gray", vmin=0, vmax=255, aspect="auto")

plt.title("Result of convolution with sobel kernel (edge detection filter)")

plt.show()

Layers

The code below initialises global variables for readability and describes the abstract class Layers. This is not important in order to understand the CNN, but is benefitial for organizing the code neatly.

import math

import autograd.numpy as np

from copy import deepcopy, copy

from autograd import grad

from typing import Callable

# global variables for index readability

input_index = 0

node_index = 1

bias_index = 1

input_channel_index = 1

feature_maps_index = 1

height_index = 2

width_index = 3

kernel_feature_maps_index = 1

kernel_input_channels_index = 0

class Layer:

def __init__(self, seed):

self.seed = seed

def _feedforward(self):

raise NotImplementedError

def _backpropagate(self):

raise NotImplementedError

def _reset_weights(self, previous_nodes):

raise NotImplementedError

Convolution2DLayer: convolution in a hidden layer

After establishing the foundational understanding of applying convolution to spatial data, let us delve into the intricate workings of a convolutional layer in a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). The primary function of convolution, as previously discussed, is to extract pertinent information from images while simultaneously decreasing the scale of our data. To initiate the image processing, we shall begin by partitioning the images into color channels (unless the image is grayscale), comprising three primary colors: red, green, and blue. We will subsequently utilize trainable kernels to construct a higher-dimensional encoding of each channel called feature maps. Successive layers will receive these feature maps as inputs, generating further encodings, albeit with reduced dimensions. The term trainable kernels denotes the initialization of pre-defined kernel-shaped weights, which we will then train via backpropagation, similar to how weights are trained in a Feedforward Neural Network.

To ensure seamless integration between our implementation of the convolutional layer and popular machine learning frameworks like Tensorflow (Keras) and PyTorch, we have adopted a design pattern that mirrors the construction of models using these APIs. This involves implementing our convolutional layer as a Python class or object, which allows for a more modular and flexible approach to building neural networks. By structuring our code in this way, users can easily incorporate our implementation into their existing machine learning pipelines without having to make significant changes to their codebase. Additionally, this design pattern promotes code reusability and makes it easier to maintain and update our convolutional layer implementation over time.

Note that the Convolution2DLayer takes in an activation function as a parameter, as it also performs non-linearity.

class Convolution2DLayer(Layer):

def __init__(

self,

input_channels,

feature_maps,

kernel_height,

kernel_width,

v_stride,

h_stride,

pad,

act_func: Callable,

seed=None,

reset_weights_independently=True,

):

super().__init__(seed)

self.input_channels = input_channels

self.feature_maps = feature_maps

self.kernel_height = kernel_height

self.kernel_width = kernel_width

self.v_stride = v_stride

self.h_stride = h_stride

self.pad = pad

self.act_func = act_func

# such that the layer can be used on its own

# outside of the CNN module

if reset_weights_independently == True:

self._reset_weights_independently()

def _feedforward(self, X_batch):

# note that the shape of X_batch = [inputs, input_maps, img_height, img_width]

# pad the input batch

X_batch_padded = self._padding(X_batch)

# calculate height_index and width_index after stride

strided_height = int(np.ceil(X_batch.shape[height_index] / self.v_stride))

strided_width = int(np.ceil(X_batch.shape[width_index] / self.h_stride))

# create output array

output = np.ndarray(

(

X_batch.shape[input_index],

self.feature_maps,

strided_height,

strided_width,

)

)

# save input and output for backpropagation

self.X_batch_feedforward = X_batch

self.output_shape = output.shape

# checking for errors, no need to look here :)

self._check_for_errors()

# convolve input with kernel

for img in range(X_batch.shape[input_index]):

for chin in range(self.input_channels):

for fmap in range(self.feature_maps):

out_h = 0

for h in range(0, X_batch.shape[height_index], self.v_stride):

out_w = 0

for w in range(0, X_batch.shape[width_index], self.h_stride):

output[img, fmap, out_h, out_w] = np.sum(

X_batch_padded[

img,

chin,

h : h + self.kernel_height,

w : w + self.kernel_width,

]

* self.kernel[chin, fmap, :, :]

)

out_w += 1

out_h += 1

# Pay attention to the fact that we're not rotating the kernel by 180 degrees when filtering the image in

# the convolutional layer, as convolution in terms of Machine Learning is a procedure known as cross-correlation

# in image processing and signal processing

# return a

return self.act_func(output / (self.kernel_height))

def _backpropagate(self, delta_term_next):

# intiate matrices

delta_term = np.zeros((self.X_batch_feedforward.shape))

gradient_kernel = np.zeros((self.kernel.shape))

# pad input for convolution

X_batch_padded = self._padding(self.X_batch_feedforward)

# Since an activation function is used at the output of the convolution layer, its derivative

# has to be accounted for in the backpropagation -> as if ReLU was a layer on its own.

act_derivative = derivate(self.act_func)

delta_term_next = act_derivative(delta_term_next)

# fill in 0's for values removed by vertical stride in feedforward

if self.v_stride > 1:

v_ind = 1

for i in range(delta_term_next.shape[height_index]):

for j in range(self.v_stride - 1):

delta_term_next = np.insert(

delta_term_next, v_ind, 0, axis=height_index

)

v_ind += self.v_stride

# fill in 0's for values removed by horizontal stride in feedforward

if self.h_stride > 1:

h_ind = 1

for i in range(delta_term_next.shape[width_index]):

for k in range(self.h_stride - 1):

delta_term_next = np.insert(

delta_term_next, h_ind, 0, axis=width_index

)

h_ind += self.h_stride

# crops out 0-rows and 0-columns

delta_term_next = delta_term_next[

:,

:,

: self.X_batch_feedforward.shape[height_index],

: self.X_batch_feedforward.shape[width_index],

]

# the gradient received from the next layer also needs to be padded

delta_term_next = self._padding(delta_term_next)

# calculate delta term by convolving next delta term with kernel

for img in range(self.X_batch_feedforward.shape[input_index]):

for chin in range(self.input_channels):

for fmap in range(self.feature_maps):

for h in range(self.X_batch_feedforward.shape[height_index]):

for w in range(self.X_batch_feedforward.shape[width_index]):

delta_term[img, chin, h, w] = np.sum(

delta_term_next[

img,

fmap,

h : h + self.kernel_height,

w : w + self.kernel_width,

]

* np.rot90(np.rot90(self.kernel[chin, fmap, :, :]))

)

# calculate gradient for kernel for weight update

# also via convolution

for chin in range(self.input_channels):

for fmap in range(self.feature_maps):

for k_x in range(self.kernel_height):

for k_y in range(self.kernel_width):

gradient_kernel[chin, fmap, k_x, k_y] = np.sum(

X_batch_padded[

img,

chin,

h : h + self.kernel_height,

w : w + self.kernel_width,

]

* delta_term_next[

img,

fmap,

h : h + self.kernel_height,

w : w + self.kernel_width,

]

)

# all kernels are updated with weight gradient of kernel

self.kernel -= gradient_kernel

# return delta term

return delta_term

def _padding(self, X_batch, batch_type="image"):

# same padding for images

if self.pad == "same" and batch_type == "image":

padded_height = X_batch.shape[height_index] + (self.kernel_height // 2) * 2

padded_width = X_batch.shape[width_index] + (self.kernel_width // 2) * 2

half_kernel_height = self.kernel_height // 2

half_kernel_width = self.kernel_width // 2

# initialize padded array

X_batch_padded = np.ndarray(

(

X_batch.shape[input_index],

X_batch.shape[feature_maps_index],

padded_height,

padded_width,

)

)

# zero pad all images in X_batch

for img in range(X_batch.shape[input_index]):

padded_img = np.zeros(

(X_batch.shape[feature_maps_index], padded_height, padded_width)

)

padded_img[

:,

half_kernel_height : padded_height - half_kernel_height,

half_kernel_width : padded_width - half_kernel_width,

] = X_batch[img, :, :, :]

X_batch_padded[img, :, :, :] = padded_img[:, :, :]

return X_batch_padded

# same padding for gradients

elif self.pad == "same" and batch_type == "grad":

padded_height = X_batch.shape[height_index] + (self.kernel_height // 2) * 2

padded_width = X_batch.shape[width_index] + (self.kernel_width // 2) * 2

half_kernel_height = self.kernel_height // 2

half_kernel_width = self.kernel_width // 2

# initialize padded array

delta_term_padded = np.zeros(

(