Week 40: Gradient descent methods (continued) and start Neural networks

September 29-October 3, 2025

Lecture Monday September 29, 2025

- Logistic regression and gradient descent, examples on how to code

- Start with the basics of Neural Networks, setting up the basic steps, from the simple perceptron model to the multi-layer perceptron model

- Video of lecture at https://youtu.be/MS3Tv8FVArs

- Whiteboard notes at https://github.com/CompPhysics/MachineLearning/blob/master/doc/HandWrittenNotes/2025/FYSSTKweek40.pdf

Suggested readings and videos

- The lecture notes for week 40 (these notes)

- For neural networks we recommend Goodfellow et al chapter 6 and Raschka et al chapter 2 (contains also material about gradient descent) and chapter 11 (we will use this next week)

- Neural Networks demystified at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxe2T-V8XRs&list=PLiaHhY2iBX9hdHaRr6b7XevZtgZRa1PoU&ab_channel=WelchLabs

- Building Neural Networks from scratch at URL:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wo5dMEP_BbI&list=PLQVvvaa0QuDcjD5BAw2DxE6OF2tius3V3&ab_channel=sentdex"

Lab sessions Tuesday and Wednesday

- Work on project 1 and discussions on how to structure your report

- No weekly exercises for week 40, project work only

- Video on how to write scientific reports recorded during one of the lab sessions at https://youtu.be/tVW1ZDmZnwM

- A general guideline can be found at https://github.com/CompPhysics/MachineLearning/blob/master/doc/Projects/EvaluationGrading/EvaluationForm.md.

Logistic Regression, from last week

In linear regression our main interest was centered on learning the coefficients of a functional fit (say a polynomial) in order to be able to predict the response of a continuous variable on some unseen data. The fit to the continuous variable \( y_i \) is based on some independent variables \( \boldsymbol{x}_i \). Linear regression resulted in analytical expressions for standard ordinary Least Squares or Ridge regression (in terms of matrices to invert) for several quantities, ranging from the variance and thereby the confidence intervals of the parameters \( \boldsymbol{\theta} \) to the mean squared error. If we can invert the product of the design matrices, linear regression gives then a simple recipe for fitting our data.

Classification problems

Classification problems, however, are concerned with outcomes taking the form of discrete variables (i.e. categories). We may for example, on the basis of DNA sequencing for a number of patients, like to find out which mutations are important for a certain disease; or based on scans of various patients' brains, figure out if there is a tumor or not; or given a specific physical system, we'd like to identify its state, say whether it is an ordered or disordered system (typical situation in solid state physics); or classify the status of a patient, whether she/he has a stroke or not and many other similar situations.

The most common situation we encounter when we apply logistic regression is that of two possible outcomes, normally denoted as a binary outcome, true or false, positive or negative, success or failure etc.

Optimization and Deep learning

Logistic regression will also serve as our stepping stone towards neural network algorithms and supervised deep learning. For logistic learning, the minimization of the cost function leads to a non-linear equation in the parameters \( \boldsymbol{\theta} \). The optimization of the problem calls therefore for minimization algorithms.

As we have discussed earlier, this forms the bottle neck of all machine learning algorithms, namely how to find reliable minima of a multi-variable function. This leads us to the family of gradient descent methods. The latter are the working horses of basically all modern machine learning algorithms.

We note also that many of the topics discussed here on logistic regression are also commonly used in modern supervised Deep Learning models, as we will see later.

Basics

We consider the case where the outputs/targets, also called the responses or the outcomes, \( y_i \) are discrete and only take values from \( k=0,\dots,K-1 \) (i.e. \( K \) classes).

The goal is to predict the output classes from the design matrix \( \boldsymbol{X}\in\mathbb{R}^{n\times p} \) made of \( n \) samples, each of which carries \( p \) features or predictors. The primary goal is to identify the classes to which new unseen samples belong.

Last week we specialized to the case of two classes only, with outputs \( y_i=0 \) and \( y_i=1 \). Our outcomes could represent the status of a credit card user that could default or not on her/his credit card debt. That is

$$

y_i = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & \mathrm{no}\\ 1 & \mathrm{yes} \end{bmatrix}.

$$

Two parameters

We assume now that we have two classes with \( y_i \) either \( 0 \) or \( 1 \). Furthermore we assume also that we have only two parameters \( \theta \) in our fitting of the Sigmoid function, that is we define probabilities

$$

\begin{align*}

p(y_i=1|x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}) &= \frac{\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i)}}{1+\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i)}},\nonumber\\

p(y_i=0|x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}) &= 1 - p(y_i=1|x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}),

\end{align*}

$$

where \( \boldsymbol{\theta} \) are the weights we wish to extract from data, in our case \( \theta_0 \) and \( \theta_1 \).

Note that we used

$$

p(y_i=0\vert x_i, \boldsymbol{\theta}) = 1-p(y_i=1\vert x_i, \boldsymbol{\theta}).

$$

Maximum likelihood

In order to define the total likelihood for all possible outcomes from a dataset \( \mathcal{D}=\{(y_i,x_i)\} \), with the binary labels \( y_i\in\{0,1\} \) and where the data points are drawn independently, we use the so-called Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) principle. We aim thus at maximizing the probability of seeing the observed data. We can then approximate the likelihood in terms of the product of the individual probabilities of a specific outcome \( y_i \), that is

$$

\begin{align*}

P(\mathcal{D}|\boldsymbol{\theta})& = \prod_{i=1}^n \left[p(y_i=1|x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta})\right]^{y_i}\left[1-p(y_i=1|x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}))\right]^{1-y_i}\nonumber \\

\end{align*}

$$

from which we obtain the log-likelihood and our cost/loss function

$$

\mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \sum_{i=1}^n \left( y_i\log{p(y_i=1|x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta})} + (1-y_i)\log\left[1-p(y_i=1|x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}))\right]\right).

$$

The cost function rewritten

Reordering the logarithms, we can rewrite the cost/loss function as

$$

\mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \sum_{i=1}^n \left(y_i(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i) -\log{(1+\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i)})}\right).

$$

The maximum likelihood estimator is defined as the set of parameters that maximize the log-likelihood where we maximize with respect to \( \theta \). Since the cost (error) function is just the negative log-likelihood, for logistic regression we have that

$$

\mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta})=-\sum_{i=1}^n \left(y_i(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i) -\log{(1+\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i)})}\right).

$$

This equation is known in statistics as the cross entropy. Finally, we note that just as in linear regression, in practice we often supplement the cross-entropy with additional regularization terms, usually \( L_1 \) and \( L_2 \) regularization as we did for Ridge and Lasso regression.

Minimizing the cross entropy

The cross entropy is a convex function of the weights \( \boldsymbol{\theta} \) and, therefore, any local minimizer is a global minimizer.

Minimizing this cost function with respect to the two parameters \( \theta_0 \) and \( \theta_1 \) we obtain

$$

\frac{\partial \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta})}{\partial \theta_0} = -\sum_{i=1}^n \left(y_i -\frac{\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i)}}{1+\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i)}}\right),

$$

and

$$

\frac{\partial \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta})}{\partial \theta_1} = -\sum_{i=1}^n \left(y_ix_i -x_i\frac{\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i)}}{1+\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i)}}\right).

$$

A more compact expression

Let us now define a vector \( \boldsymbol{y} \) with \( n \) elements \( y_i \), an \( n\times p \) matrix \( \boldsymbol{X} \) which contains the \( x_i \) values and a vector \( \boldsymbol{p} \) of fitted probabilities \( p(y_i\vert x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}) \). We can rewrite in a more compact form the first derivative of the cost function as

$$

\frac{\partial \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta})}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}} = -\boldsymbol{X}^T\left(\boldsymbol{y}-\boldsymbol{p}\right).

$$

If we in addition define a diagonal matrix \( \boldsymbol{W} \) with elements \( p(y_i\vert x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta})(1-p(y_i\vert x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}) \), we can obtain a compact expression of the second derivative as

$$

\frac{\partial^2 \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta})}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}^T} = \boldsymbol{X}^T\boldsymbol{W}\boldsymbol{X}.

$$

Extending to more predictors

Within a binary classification problem, we can easily expand our model to include multiple predictors. Our ratio between likelihoods is then with \( p \) predictors

$$

\log{ \frac{p(\boldsymbol{\theta}\boldsymbol{x})}{1-p(\boldsymbol{\theta}\boldsymbol{x})}} = \theta_0+\theta_1x_1+\theta_2x_2+\dots+\theta_px_p.

$$

Here we defined \( \boldsymbol{x}=[1,x_1,x_2,\dots,x_p] \) and \( \boldsymbol{\theta}=[\theta_0, \theta_1, \dots, \theta_p] \) leading to

$$

p(\boldsymbol{\theta}\boldsymbol{x})=\frac{ \exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_1+\theta_2x_2+\dots+\theta_px_p)}}{1+\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_1+\theta_2x_2+\dots+\theta_px_p)}}.

$$

Including more classes

Till now we have mainly focused on two classes, the so-called binary system. Suppose we wish to extend to \( K \) classes. Let us for the sake of simplicity assume we have only two predictors. We have then following model

$$

\log{\frac{p(C=1\vert x)}{p(K\vert x)}} = \theta_{10}+\theta_{11}x_1,

$$

and

$$

\log{\frac{p(C=2\vert x)}{p(K\vert x)}} = \theta_{20}+\theta_{21}x_1,

$$

and so on till the class \( C=K-1 \) class

$$

\log{\frac{p(C=K-1\vert x)}{p(K\vert x)}} = \theta_{(K-1)0}+\theta_{(K-1)1}x_1,

$$

and the model is specified in term of \( K-1 \) so-called log-odds or logit transformations.

More classes

In our discussion of neural networks we will encounter the above again in terms of a slightly modified function, the so-called Softmax function.

The softmax function is used in various multiclass classification methods, such as multinomial logistic regression (also known as softmax regression), multiclass linear discriminant analysis, naive Bayes classifiers, and artificial neural networks. Specifically, in multinomial logistic regression and linear discriminant analysis, the input to the function is the result of \( K \) distinct linear functions, and the predicted probability for the \( k \)-th class given a sample vector \( \boldsymbol{x} \) and a weighting vector \( \boldsymbol{\theta} \) is (with two predictors):

$$

p(C=k\vert \mathbf {x} )=\frac{\exp{(\theta_{k0}+\theta_{k1}x_1)}}{1+\sum_{l=1}^{K-1}\exp{(\theta_{l0}+\theta_{l1}x_1)}}.

$$

It is easy to extend to more predictors. The final class is

$$

p(C=K\vert \mathbf {x} )=\frac{1}{1+\sum_{l=1}^{K-1}\exp{(\theta_{l0}+\theta_{l1}x_1)}},

$$

and they sum to one. Our earlier discussions were all specialized to the case with two classes only. It is easy to see from the above that what we derived earlier is compatible with these equations.

To find the optimal parameters we would typically use a gradient descent method. Newton's method and gradient descent methods are discussed in the material on optimization methods.

Optimization, the central part of any Machine Learning algortithm

Almost every problem in machine learning and data science starts with a dataset \( X \), a model \( g(\theta) \), which is a function of the parameters \( \theta \) and a cost function \( C(X, g(\theta)) \) that allows us to judge how well the model \( g(\theta) \) explains the observations \( X \). The model is fit by finding the values of \( \theta \) that minimize the cost function. Ideally we would be able to solve for \( \theta \) analytically, however this is not possible in general and we must use some approximative/numerical method to compute the minimum.

Revisiting our Logistic Regression case

In our discussion on Logistic Regression we studied the case of two classes, with \( y_i \) either \( 0 \) or \( 1 \). Furthermore we assumed also that we have only two parameters \( \theta \) in our fitting, that is we defined probabilities

$$

\begin{align*}

p(y_i=1|x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}) &= \frac{\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i)}}{1+\exp{(\theta_0+\theta_1x_i)}},\nonumber\\

p(y_i=0|x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}) &= 1 - p(y_i=1|x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}),

\end{align*}

$$

where \( \boldsymbol{\theta} \) are the weights we wish to extract from data, in our case \( \theta_0 \) and \( \theta_1 \).

The equations to solve

Our compact equations used a definition of a vector \( \boldsymbol{y} \) with \( n \) elements \( y_i \), an \( n\times p \) matrix \( \boldsymbol{X} \) which contains the \( x_i \) values and a vector \( \boldsymbol{p} \) of fitted probabilities \( p(y_i\vert x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}) \). We rewrote in a more compact form the first derivative of the cost function as

$$

\frac{\partial \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta})}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}} = -\boldsymbol{X}^T\left(\boldsymbol{y}-\boldsymbol{p}\right).

$$

If we in addition define a diagonal matrix \( \boldsymbol{W} \) with elements \( p(y_i\vert x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta})(1-p(y_i\vert x_i,\boldsymbol{\theta}) \), we can obtain a compact expression of the second derivative as

$$

\frac{\partial^2 \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta})}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}^T} = \boldsymbol{X}^T\boldsymbol{W}\boldsymbol{X}.

$$

This defines what is called the Hessian matrix.

Solving using Newton-Raphson's method

If we can set up these equations, Newton-Raphson's iterative method is normally the method of choice. It requires however that we can compute in an efficient way the matrices that define the first and second derivatives.

Our iterative scheme is then given by

$$

\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathrm{new}} = \boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathrm{old}}-\left(\frac{\partial^2 \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta})}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}^T}\right)^{-1}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathrm{old}}}\times \left(\frac{\partial \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{\theta})}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}}\right)_{\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathrm{old}}},

$$

or in matrix form as

$$

\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathrm{new}} = \boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathrm{old}}-\left(\boldsymbol{X}^T\boldsymbol{W}\boldsymbol{X} \right)^{-1}\times \left(-\boldsymbol{X}^T(\boldsymbol{y}-\boldsymbol{p}) \right)_{\boldsymbol{\theta}^{\mathrm{old}}}.

$$

The right-hand side is computed with the old values of \( \theta \).

If we can compute these matrices, in particular the Hessian, the above is often the easiest method to implement.

Example code for Logistic Regression

Here we make a class for Logistic regression. The code uses a simple data set and includes both a binary case and a multiclass case.

import numpy as np

class LogisticRegression:

"""

Logistic Regression for binary and multiclass classification.

"""

def __init__(self, lr=0.01, epochs=1000, fit_intercept=True, verbose=False):

self.lr = lr # Learning rate for gradient descent

self.epochs = epochs # Number of iterations

self.fit_intercept = fit_intercept # Whether to add intercept (bias)

self.verbose = verbose # Print loss during training if True

self.weights = None

self.multi_class = False # Will be determined at fit time

def _add_intercept(self, X):

"""Add intercept term (column of ones) to feature matrix."""

intercept = np.ones((X.shape[0], 1))

return np.concatenate((intercept, X), axis=1)

def _sigmoid(self, z):

"""Sigmoid function for binary logistic."""

return 1 / (1 + np.exp(-z))

def _softmax(self, Z):

"""Softmax function for multiclass logistic."""

exp_Z = np.exp(Z - np.max(Z, axis=1, keepdims=True))

return exp_Z / np.sum(exp_Z, axis=1, keepdims=True)

def fit(self, X, y):

"""

Train the logistic regression model using gradient descent.

Supports binary (sigmoid) and multiclass (softmax) based on y.

"""

X = np.array(X)

y = np.array(y)

n_samples, n_features = X.shape

# Add intercept if needed

if self.fit_intercept:

X = self._add_intercept(X)

n_features += 1

# Determine classes and mode (binary vs multiclass)

unique_classes = np.unique(y)

if len(unique_classes) > 2:

self.multi_class = True

else:

self.multi_class = False

# ----- Multiclass case -----

if self.multi_class:

n_classes = len(unique_classes)

# Map original labels to 0...n_classes-1

class_to_index = {c: idx for idx, c in enumerate(unique_classes)}

y_indices = np.array([class_to_index[c] for c in y])

# Initialize weight matrix (features x classes)

self.weights = np.zeros((n_features, n_classes))

# One-hot encode y

Y_onehot = np.zeros((n_samples, n_classes))

Y_onehot[np.arange(n_samples), y_indices] = 1

# Gradient descent

for epoch in range(self.epochs):

scores = X.dot(self.weights) # Linear scores (n_samples x n_classes)

probs = self._softmax(scores) # Probabilities (n_samples x n_classes)

# Compute gradient (features x classes)

gradient = (1 / n_samples) * X.T.dot(probs - Y_onehot)

# Update weights

self.weights -= self.lr * gradient

if self.verbose and epoch % 100 == 0:

# Compute current loss (categorical cross-entropy)

loss = -np.sum(Y_onehot * np.log(probs + 1e-15)) / n_samples

print(f"[Epoch {epoch}] Multiclass loss: {loss:.4f}")

# ----- Binary case -----

else:

# Convert y to 0/1 if not already

if not np.array_equal(unique_classes, [0, 1]):

# Map the two classes to 0 and 1

class0, class1 = unique_classes

y_binary = np.where(y == class1, 1, 0)

else:

y_binary = y.copy().astype(int)

# Initialize weights vector (features,)

self.weights = np.zeros(n_features)

# Gradient descent

for epoch in range(self.epochs):

linear_model = X.dot(self.weights) # (n_samples,)

probs = self._sigmoid(linear_model) # (n_samples,)

# Gradient for binary cross-entropy

gradient = (1 / n_samples) * X.T.dot(probs - y_binary)

self.weights -= self.lr * gradient

if self.verbose and epoch % 100 == 0:

# Compute binary cross-entropy loss

loss = -np.mean(

y_binary * np.log(probs + 1e-15) +

(1 - y_binary) * np.log(1 - probs + 1e-15)

)

print(f"[Epoch {epoch}] Binary loss: {loss:.4f}")

def predict_prob(self, X):

"""

Compute probability estimates. Returns a 1D array for binary or

a 2D array (n_samples x n_classes) for multiclass.

"""

X = np.array(X)

# Add intercept if the model used it

if self.fit_intercept:

X = self._add_intercept(X)

scores = X.dot(self.weights)

if self.multi_class:

return self._softmax(scores)

else:

return self._sigmoid(scores)

def predict(self, X):

"""

Predict class labels for samples in X.

Returns integer class labels (0,1 for binary, or 0...C-1 for multiclass).

"""

probs = self.predict_prob(X)

if self.multi_class:

# Choose class with highest probability

return np.argmax(probs, axis=1)

else:

# Threshold at 0.5 for binary

return (probs >= 0.5).astype(int)

The class implements the sigmoid and softmax internally. During fit(), we check the number of classes: if more than 2, we set self.multi_class=True and perform multinomial logistic regression. We one-hot encode the target vector and update a weight matrix with softmax probabilities. Otherwise, we do standard binary logistic regression, converting labels to 0/1 if needed and updating a weight vector. In both cases we use batch gradient descent on the cross-entropy loss (we add a small epsilon 1e-15 to logs for numerical stability). Progress (loss) can be printed if verbose=True.

# Evaluation Metrics

#We define helper functions for accuracy and cross-entropy loss. Accuracy is the fraction of correct predictions . For loss, we compute the appropriate cross-entropy:

def accuracy_score(y_true, y_pred):

"""Accuracy = (# correct predictions) / (total samples)."""

y_true = np.array(y_true)

y_pred = np.array(y_pred)

return np.mean(y_true == y_pred)

def binary_cross_entropy(y_true, y_prob):

"""

Binary cross-entropy loss.

y_true: true binary labels (0 or 1), y_prob: predicted probabilities for class 1.

"""

y_true = np.array(y_true)

y_prob = np.clip(np.array(y_prob), 1e-15, 1-1e-15)

return -np.mean(y_true * np.log(y_prob) + (1 - y_true) * np.log(1 - y_prob))

def categorical_cross_entropy(y_true, y_prob):

"""

Categorical cross-entropy loss for multiclass.

y_true: true labels (0...C-1), y_prob: array of predicted probabilities (n_samples x C).

"""

y_true = np.array(y_true, dtype=int)

y_prob = np.clip(np.array(y_prob), 1e-15, 1-1e-15)

# One-hot encode true labels

n_samples, n_classes = y_prob.shape

one_hot = np.zeros_like(y_prob)

one_hot[np.arange(n_samples), y_true] = 1

# Compute cross-entropy

loss_vec = -np.sum(one_hot * np.log(y_prob), axis=1)

return np.mean(loss_vec)

Synthetic data generation

Binary classification data: Create two Gaussian clusters in 2D. For example, class 0 around mean [-2,-2] and class 1 around [2,2]. Multiclass data: Create several Gaussian clusters (one per class) spread out in feature space.

import numpy as np

def generate_binary_data(n_samples=100, n_features=2, random_state=None):

"""

Generate synthetic binary classification data.

Returns (X, y) where X is (n_samples x n_features), y in {0,1}.

"""

rng = np.random.RandomState(random_state)

# Half samples for class 0, half for class 1

n0 = n_samples // 2

n1 = n_samples - n0

# Class 0 around mean -2, class 1 around +2

mean0 = -2 * np.ones(n_features)

mean1 = 2 * np.ones(n_features)

X0 = rng.randn(n0, n_features) + mean0

X1 = rng.randn(n1, n_features) + mean1

X = np.vstack((X0, X1))

y = np.array([0]*n0 + [1]*n1)

return X, y

def generate_multiclass_data(n_samples=150, n_features=2, n_classes=3, random_state=None):

"""

Generate synthetic multiclass data with n_classes Gaussian clusters.

"""

rng = np.random.RandomState(random_state)

X = []

y = []

samples_per_class = n_samples // n_classes

for cls in range(n_classes):

# Random cluster center for each class

center = rng.uniform(-5, 5, size=n_features)

Xi = rng.randn(samples_per_class, n_features) + center

yi = [cls] * samples_per_class

X.append(Xi)

y.extend(yi)

X = np.vstack(X)

y = np.array(y)

return X, y

# Generate and test on binary data

X_bin, y_bin = generate_binary_data(n_samples=200, n_features=2, random_state=42)

model_bin = LogisticRegression(lr=0.1, epochs=1000)

model_bin.fit(X_bin, y_bin)

y_prob_bin = model_bin.predict_prob(X_bin) # probabilities for class 1

y_pred_bin = model_bin.predict(X_bin) # predicted classes 0 or 1

acc_bin = accuracy_score(y_bin, y_pred_bin)

loss_bin = binary_cross_entropy(y_bin, y_prob_bin)

print(f"Binary Classification - Accuracy: {acc_bin:.2f}, Cross-Entropy Loss: {loss_bin:.2f}")

#For multiclass:

# Generate and test on multiclass data

X_multi, y_multi = generate_multiclass_data(n_samples=300, n_features=2, n_classes=3, random_state=1)

model_multi = LogisticRegression(lr=0.1, epochs=1000)

model_multi.fit(X_multi, y_multi)

y_prob_multi = model_multi.predict_prob(X_multi) # (n_samples x 3) probabilities

y_pred_multi = model_multi.predict(X_multi) # predicted labels 0,1,2

acc_multi = accuracy_score(y_multi, y_pred_multi)

loss_multi = categorical_cross_entropy(y_multi, y_prob_multi)

print(f"Multiclass Classification - Accuracy: {acc_multi:.2f}, Cross-Entropy Loss: {loss_multi:.2f}")

# CSV Export

import csv

# Export binary results

with open('binary_results.csv', mode='w', newline='') as f:

writer = csv.writer(f)

writer.writerow(["TrueLabel", "PredictedLabel"])

for true, pred in zip(y_bin, y_pred_bin):

writer.writerow([true, pred])

# Export multiclass results

with open('multiclass_results.csv', mode='w', newline='') as f:

writer = csv.writer(f)

writer.writerow(["TrueLabel", "PredictedLabel"])

for true, pred in zip(y_multi, y_pred_multi):

writer.writerow([true, pred])

Using Scikit-learn

We show here how we can use a logistic regression case on a data set included in _scikit_learn_, the so-called Wisconsin breast cancer data using Logistic regression as our algorithm for classification. This is a widely studied data set and can easily be included in demonstrations of classification problems.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

# Load the data

cancer = load_breast_cancer()

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(cancer.data,cancer.target,random_state=0)

print(X_train.shape)

print(X_test.shape)

# Logistic Regression

logreg = LogisticRegression(solver='lbfgs')

logreg.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("Test set accuracy with Logistic Regression: {:.2f}".format(logreg.score(X_test,y_test)))

Using the correlation matrix

In addition to the above scores, we could also study the covariance (and the correlation matrix). We use Pandas to compute the correlation matrix.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

cancer = load_breast_cancer()

import pandas as pd

# Making a data frame

cancerpd = pd.DataFrame(cancer.data, columns=cancer.feature_names)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(15,2,figsize=(10,20))

malignant = cancer.data[cancer.target == 0]

benign = cancer.data[cancer.target == 1]

ax = axes.ravel()

for i in range(30):

_, bins = np.histogram(cancer.data[:,i], bins =50)

ax[i].hist(malignant[:,i], bins = bins, alpha = 0.5)

ax[i].hist(benign[:,i], bins = bins, alpha = 0.5)

ax[i].set_title(cancer.feature_names[i])

ax[i].set_yticks(())

ax[0].set_xlabel("Feature magnitude")

ax[0].set_ylabel("Frequency")

ax[0].legend(["Malignant", "Benign"], loc ="best")

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

import seaborn as sns

correlation_matrix = cancerpd.corr().round(1)

# use the heatmap function from seaborn to plot the correlation matrix

# annot = True to print the values inside the square

plt.figure(figsize=(15,8))

sns.heatmap(data=correlation_matrix, annot=True)

plt.show()

Discussing the correlation data

In the above example we note two things. In the first plot we display the overlap of benign and malignant tumors as functions of the various features in the Wisconsin data set. We see that for some of the features we can distinguish clearly the benign and malignant cases while for other features we cannot. This can point to us which features may be of greater interest when we wish to classify a benign or not benign tumour.

In the second figure we have computed the so-called correlation matrix, which in our case with thirty features becomes a \( 30\times 30 \) matrix.

We constructed this matrix using pandas via the statements

cancerpd = pd.DataFrame(cancer.data, columns=cancer.feature_names)

and then

correlation_matrix = cancerpd.corr().round(1)

Diagonalizing this matrix we can in turn say something about which features are of relevance and which are not. This leads us to the classical Principal Component Analysis (PCA) theorem with applications. This will be discussed later this semester.

Other measures in classification studies

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

# Load the data

cancer = load_breast_cancer()

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(cancer.data,cancer.target,random_state=0)

print(X_train.shape)

print(X_test.shape)

# Logistic Regression

logreg = LogisticRegression(solver='lbfgs')

logreg.fit(X_train, y_train)

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_validate

#Cross validation

accuracy = cross_validate(logreg,X_test,y_test,cv=10)['test_score']

print(accuracy)

print("Test set accuracy with Logistic Regression: {:.2f}".format(logreg.score(X_test,y_test)))

import scikitplot as skplt

y_pred = logreg.predict(X_test)

skplt.metrics.plot_confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred, normalize=True)

plt.show()

y_probas = logreg.predict_proba(X_test)

skplt.metrics.plot_roc(y_test, y_probas)

plt.show()

skplt.metrics.plot_cumulative_gain(y_test, y_probas)

plt.show()

Introduction to Neural networks

Artificial neural networks are computational systems that can learn to perform tasks by considering examples, generally without being programmed with any task-specific rules. It is supposed to mimic a biological system, wherein neurons interact by sending signals in the form of mathematical functions between layers. All layers can contain an arbitrary number of neurons, and each connection is represented by a weight variable.

Artificial neurons

The field of artificial neural networks has a long history of development, and is closely connected with the advancement of computer science and computers in general. A model of artificial neurons was first developed by McCulloch and Pitts in 1943 to study signal processing in the brain and has later been refined by others. The general idea is to mimic neural networks in the human brain, which is composed of billions of neurons that communicate with each other by sending electrical signals. Each neuron accumulates its incoming signals, which must exceed an activation threshold to yield an output. If the threshold is not overcome, the neuron remains inactive, i.e. has zero output.

This behaviour has inspired a simple mathematical model for an artificial neuron.

$$

\begin{equation}

y = f\left(\sum_{i=1}^n w_ix_i\right) = f(u)

\tag{1}

\end{equation}

$$

Here, the output \( y \) of the neuron is the value of its activation function, which have as input a weighted sum of signals \( x_i, \dots ,x_n \) received by \( n \) other neurons.

Conceptually, it is helpful to divide neural networks into four categories:

- general purpose neural networks for supervised learning,

- neural networks designed specifically for image processing, the most prominent example of this class being Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs),

- neural networks for sequential data such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and

- neural networks for unsupervised learning such as Deep Boltzmann Machines.

In natural science, DNNs and CNNs have already found numerous applications. In statistical physics, they have been applied to detect phase transitions in 2D Ising and Potts models, lattice gauge theories, and different phases of polymers, or solving the Navier-Stokes equation in weather forecasting. Deep learning has also found interesting applications in quantum physics. Various quantum phase transitions can be detected and studied using DNNs and CNNs, topological phases, and even non-equilibrium many-body localization. Representing quantum states as DNNs quantum state tomography are among some of the impressive achievements to reveal the potential of DNNs to facilitate the study of quantum systems.

In quantum information theory, it has been shown that one can perform gate decompositions with the help of neural.

The applications are not limited to the natural sciences. There is a plethora of applications in essentially all disciplines, from the humanities to life science and medicine.

Neural network types

An artificial neural network (ANN), is a computational model that consists of layers of connected neurons, or nodes or units. We will refer to these interchangeably as units or nodes, and sometimes as neurons.

It is supposed to mimic a biological nervous system by letting each neuron interact with other neurons by sending signals in the form of mathematical functions between layers. A wide variety of different ANNs have been developed, but most of them consist of an input layer, an output layer and eventual layers in-between, called hidden layers. All layers can contain an arbitrary number of nodes, and each connection between two nodes is associated with a weight variable.

Neural networks (also called neural nets) are neural-inspired nonlinear models for supervised learning. As we will see, neural nets can be viewed as natural, more powerful extensions of supervised learning methods such as linear and logistic regression and soft-max methods we discussed earlier.

Feed-forward neural networks

The feed-forward neural network (FFNN) was the first and simplest type of ANNs that were devised. In this network, the information moves in only one direction: forward through the layers.

Nodes are represented by circles, while the arrows display the connections between the nodes, including the direction of information flow. Additionally, each arrow corresponds to a weight variable (figure to come). We observe that each node in a layer is connected to all nodes in the subsequent layer, making this a so-called fully-connected FFNN.

Convolutional Neural Network

A different variant of FFNNs are convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which have a connectivity pattern inspired by the animal visual cortex. Individual neurons in the visual cortex only respond to stimuli from small sub-regions of the visual field, called a receptive field. This makes the neurons well-suited to exploit the strong spatially local correlation present in natural images. The response of each neuron can be approximated mathematically as a convolution operation. (figure to come)

Convolutional neural networks emulate the behaviour of neurons in the visual cortex by enforcing a local connectivity pattern between nodes of adjacent layers: Each node in a convolutional layer is connected only to a subset of the nodes in the previous layer, in contrast to the fully-connected FFNN. Often, CNNs consist of several convolutional layers that learn local features of the input, with a fully-connected layer at the end, which gathers all the local data and produces the outputs. They have wide applications in image and video recognition.

Recurrent neural networks

So far we have only mentioned ANNs where information flows in one direction: forward. Recurrent neural networks on the other hand, have connections between nodes that form directed cycles. This creates a form of internal memory which are able to capture information on what has been calculated before; the output is dependent on the previous computations. Recurrent NNs make use of sequential information by performing the same task for every element in a sequence, where each element depends on previous elements. An example of such information is sentences, making recurrent NNs especially well-suited for handwriting and speech recognition.

Other types of networks

There are many other kinds of ANNs that have been developed. One type that is specifically designed for interpolation in multidimensional space is the radial basis function (RBF) network. RBFs are typically made up of three layers: an input layer, a hidden layer with non-linear radial symmetric activation functions and a linear output layer (''linear'' here means that each node in the output layer has a linear activation function). The layers are normally fully-connected and there are no cycles, thus RBFs can be viewed as a type of fully-connected FFNN. They are however usually treated as a separate type of NN due the unusual activation functions.

Multilayer perceptrons

One uses often so-called fully-connected feed-forward neural networks with three or more layers (an input layer, one or more hidden layers and an output layer) consisting of neurons that have non-linear activation functions.

Such networks are often called multilayer perceptrons (MLPs).

Why multilayer perceptrons?

According to the Universal approximation theorem, a feed-forward neural network with just a single hidden layer containing a finite number of neurons can approximate a continuous multidimensional function to arbitrary accuracy, assuming the activation function for the hidden layer is a non-constant, bounded and monotonically-increasing continuous function.

Note that the requirements on the activation function only applies to the hidden layer, the output nodes are always assumed to be linear, so as to not restrict the range of output values.

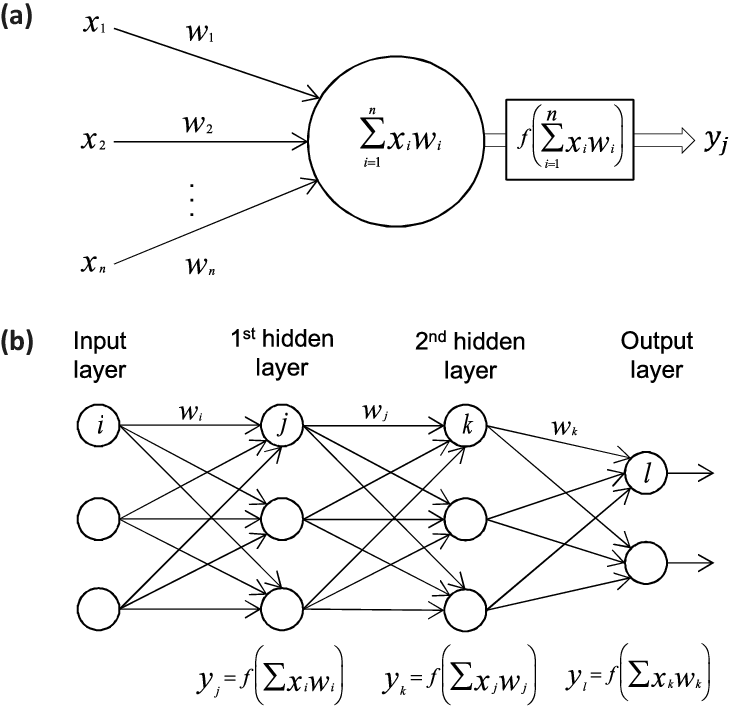

Illustration of a single perceptron model and a multi-perceptron model

Figure 1: In a) we show a single perceptron model while in b) we dispay a network with two hidden layers, an input layer and an output layer.

Examples of XOR, OR and AND gates

Let us first try to fit various gates using standard linear regression. The gates we are thinking of are the classical XOR, OR and AND gates, well-known elements in computer science. The tables here show how we can set up the inputs \( x_1 \) and \( x_2 \) in order to yield a specific target \( y_i \).

"""

Simple code that tests XOR, OR and AND gates with linear regression

"""

import numpy as np

# Design matrix

X = np.array([ [1, 0, 0], [1, 0, 1], [1, 1, 0],[1, 1, 1]],dtype=np.float64)

print(f"The X.TX matrix:{X.T @ X}")

Xinv = np.linalg.pinv(X.T @ X)

print(f"The invers of X.TX matrix:{Xinv}")

# The XOR gate

yXOR = np.array( [ 0, 1 ,1, 0])

ThetaXOR = Xinv @ X.T @ yXOR

print(f"The values of theta for the XOR gate:{ThetaXOR}")

print(f"The linear regression prediction for the XOR gate:{X @ ThetaXOR}")

# The OR gate

yOR = np.array( [ 0, 1 ,1, 1])

ThetaOR = Xinv @ X.T @ yOR

print(f"The values of theta for the OR gate:{ThetaOR}")

print(f"The linear regression prediction for the OR gate:{X @ ThetaOR}")

# The OR gate

yAND = np.array( [ 0, 0 ,0, 1])

ThetaAND = Xinv @ X.T @ yAND

print(f"The values of theta for the AND gate:{ThetaAND}")

print(f"The linear regression prediction for the AND gate:{X @ ThetaAND}")

What is happening here?

Does Logistic Regression do a better Job?

"""

Simple code that tests XOR and OR gates with linear regression

and logistic regression

"""

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

import numpy as np

# Design matrix

X = np.array([ [1, 0, 0], [1, 0, 1], [1, 1, 0],[1, 1, 1]],dtype=np.float64)

print(f"The X.TX matrix:{X.T @ X}")

Xinv = np.linalg.pinv(X.T @ X)

print(f"The invers of X.TX matrix:{Xinv}")

# The XOR gate

yXOR = np.array( [ 0, 1 ,1, 0])

ThetaXOR = Xinv @ X.T @ yXOR

print(f"The values of theta for the XOR gate:{ThetaXOR}")

print(f"The linear regression prediction for the XOR gate:{X @ ThetaXOR}")

# The OR gate

yOR = np.array( [ 0, 1 ,1, 1])

ThetaOR = Xinv @ X.T @ yOR

print(f"The values of theta for the OR gate:{ThetaOR}")

print(f"The linear regression prediction for the OR gate:{X @ ThetaOR}")

# The OR gate

yAND = np.array( [ 0, 0 ,0, 1])

ThetaAND = Xinv @ X.T @ yAND

print(f"The values of theta for the AND gate:{ThetaAND}")

print(f"The linear regression prediction for the AND gate:{X @ ThetaAND}")

# Now we change to logistic regression

# Logistic Regression

logreg = LogisticRegression()

logreg.fit(X, yOR)

print("Test set accuracy with Logistic Regression for OR gate: {:.2f}".format(logreg.score(X,yOR)))

logreg.fit(X, yXOR)

print("Test set accuracy with Logistic Regression for XOR gate: {:.2f}".format(logreg.score(X,yXOR)))

logreg.fit(X, yAND)

print("Test set accuracy with Logistic Regression for AND gate: {:.2f}".format(logreg.score(X,yAND)))

Not exactly impressive, but somewhat better.

Adding Neural Networks

# and now neural networks with Scikit-Learn and the XOR

from sklearn.neural_network import MLPClassifier

from sklearn.datasets import make_classification

X, yXOR = make_classification(n_samples=100, random_state=1)

FFNN = MLPClassifier(random_state=1, max_iter=300).fit(X, yXOR)

FFNN.predict_proba(X)

print(f"Test set accuracy with Feed Forward Neural Network for XOR gate:{FFNN.score(X, yXOR)}")

Mathematical model

The output \( y \) is produced via the activation function \( f \)

$$

y = f\left(\sum_{i=1}^n w_ix_i + b_i\right) = f(z),

$$

This function receives \( x_i \) as inputs. Here the activation \( z=(\sum_{i=1}^n w_ix_i+b_i) \). In an FFNN of such neurons, the inputs \( x_i \) are the outputs of the neurons in the preceding layer. Furthermore, an MLP is fully-connected, which means that each neuron receives a weighted sum of the outputs of all neurons in the previous layer.

Mathematical model

First, for each node \( i \) in the first hidden layer, we calculate a weighted sum \( z_i^1 \) of the input coordinates \( x_j \),

$$

\begin{equation} z_i^1 = \sum_{j=1}^{M} w_{ij}^1 x_j + b_i^1

\tag{2}

\end{equation}

$$

Here \( b_i \) is the so-called bias which is normally needed in case of zero activation weights or inputs. How to fix the biases and the weights will be discussed below. The value of \( z_i^1 \) is the argument to the activation function \( f_i \) of each node \( i \), The variable \( M \) stands for all possible inputs to a given node \( i \) in the first layer. We define the output \( y_i^1 \) of all neurons in layer 1 as

$$

\begin{equation}

y_i^1 = f(z_i^1) = f\left(\sum_{j=1}^M w_{ij}^1 x_j + b_i^1\right)

\tag{3}

\end{equation}

$$

where we assume that all nodes in the same layer have identical activation functions, hence the notation \( f \). In general, we could assume in the more general case that different layers have different activation functions. In this case we would identify these functions with a superscript \( l \) for the \( l \)-th layer,

$$

\begin{equation}

y_i^l = f^l(u_i^l) = f^l\left(\sum_{j=1}^{N_{l-1}} w_{ij}^l y_j^{l-1} + b_i^l\right)

\tag{4}

\end{equation}

$$

where \( N_l \) is the number of nodes in layer \( l \). When the output of all the nodes in the first hidden layer are computed, the values of the subsequent layer can be calculated and so forth until the output is obtained.

Mathematical model

The output of neuron \( i \) in layer 2 is thus,

$$

\begin{align}

y_i^2 &= f^2\left(\sum_{j=1}^N w_{ij}^2 y_j^1 + b_i^2\right)

\tag{5}\\

&= f^2\left[\sum_{j=1}^N w_{ij}^2f^1\left(\sum_{k=1}^M w_{jk}^1 x_k + b_j^1\right) + b_i^2\right]

\tag{6}

\end{align}

$$

where we have substituted \( y_k^1 \) with the inputs \( x_k \). Finally, the ANN output reads

$$

\begin{align}

y_i^3 &= f^3\left(\sum_{j=1}^N w_{ij}^3 y_j^2 + b_i^3\right)

\tag{7}\\

&= f_3\left[\sum_{j} w_{ij}^3 f^2\left(\sum_{k} w_{jk}^2 f^1\left(\sum_{m} w_{km}^1 x_m + b_k^1\right) + b_j^2\right)

+ b_1^3\right]

\tag{8}

\end{align}

$$

Mathematical model

We can generalize this expression to an MLP with \( l \) hidden layers. The complete functional form is,

$$

\begin{align}

&y^{l+1}_i = f^{l+1}\left[\!\sum_{j=1}^{N_l} w_{ij}^3 f^l\left(\sum_{k=1}^{N_{l-1}}w_{jk}^{l-1}\left(\dots f^1\left(\sum_{n=1}^{N_0} w_{mn}^1 x_n+ b_m^1\right)\dots\right)+b_k^2\right)+b_1^3\right] &&

\tag{9}

\end{align}

$$

which illustrates a basic property of MLPs: The only independent variables are the input values \( x_n \).

Mathematical model

This confirms that an MLP, despite its quite convoluted mathematical form, is nothing more than an analytic function, specifically a mapping of real-valued vectors \( \hat{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \hat{y} \in \mathbb{R}^m \).

Furthermore, the flexibility and universality of an MLP can be illustrated by realizing that the expression is essentially a nested sum of scaled activation functions of the form

$$

\begin{equation}

f(x) = c_1 f(c_2 x + c_3) + c_4

\tag{10}

\end{equation}

$$

where the parameters \( c_i \) are weights and biases. By adjusting these parameters, the activation functions can be shifted up and down or left and right, change slope or be rescaled which is the key to the flexibility of a neural network.

Matrix-vector notation

We can introduce a more convenient notation for the activations in an A NN.

Additionally, we can represent the biases and activations as layer-wise column vectors \( \hat{b}_l \) and \( \hat{y}_l \), so that the \( i \)-th element of each vector is the bias \( b_i^l \) and activation \( y_i^l \) of node \( i \) in layer \( l \) respectively.

We have that \( \mathrm{W}_l \) is an \( N_{l-1} \times N_l \) matrix, while \( \hat{b}_l \) and \( \hat{y}_l \) are \( N_l \times 1 \) column vectors. With this notation, the sum becomes a matrix-vector multiplication, and we can write the equation for the activations of hidden layer 2 (assuming three nodes for simplicity) as

$$

\begin{equation}

\hat{y}_2 = f_2(\mathrm{W}_2 \hat{y}_{1} + \hat{b}_{2}) =

f_2\left(\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

w^2_{11} &w^2_{12} &w^2_{13} \\

w^2_{21} &w^2_{22} &w^2_{23} \\

w^2_{31} &w^2_{32} &w^2_{33} \\

\end{array} \right] \cdot

\left[\begin{array}{c}

y^1_1 \\

y^1_2 \\

y^1_3 \\

\end{array}\right] +

\left[\begin{array}{c}

b^2_1 \\

b^2_2 \\

b^2_3 \\

\end{array}\right]\right).

\tag{11}

\end{equation}

$$

Matrix-vector notation and activation

The activation of node \( i \) in layer 2 is

$$

\begin{equation}

y^2_i = f_2\Bigr(w^2_{i1}y^1_1 + w^2_{i2}y^1_2 + w^2_{i3}y^1_3 + b^2_i\Bigr) =

f_2\left(\sum_{j=1}^3 w^2_{ij} y_j^1 + b^2_i\right).

\tag{12}

\end{equation}

$$

This is not just a convenient and compact notation, but also a useful and intuitive way to think about MLPs: The output is calculated by a series of matrix-vector multiplications and vector additions that are used as input to the activation functions. For each operation \( \mathrm{W}_l \hat{y}_{l-1} \) we move forward one layer.

Activation functions

A property that characterizes a neural network, other than its connectivity, is the choice of activation function(s). As described in, the following restrictions are imposed on an activation function for a FFNN to fulfill the universal approximation theorem

- Non-constant

- Bounded

- Monotonically-increasing

- Continuous

Activation functions, Logistic and Hyperbolic ones

The second requirement excludes all linear functions. Furthermore, in a MLP with only linear activation functions, each layer simply performs a linear transformation of its inputs.

Regardless of the number of layers, the output of the NN will be nothing but a linear function of the inputs. Thus we need to introduce some kind of non-linearity to the NN to be able to fit non-linear functions Typical examples are the logistic Sigmoid

$$

f(x) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-x}},

$$

and the hyperbolic tangent function

$$

f(x) = \tanh(x)

$$

Relevance

The sigmoid function are more biologically plausible because the output of inactive neurons are zero. Such activation function are called one-sided. However, it has been shown that the hyperbolic tangent performs better than the sigmoid for training MLPs. has become the most popular for deep neural networks

"""The sigmoid function (or the logistic curve) is a

function that takes any real number, z, and outputs a number (0,1).

It is useful in neural networks for assigning weights on a relative scale.

The value z is the weighted sum of parameters involved in the learning algorithm."""

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import math as mt

z = numpy.arange(-5, 5, .1)

sigma_fn = numpy.vectorize(lambda z: 1/(1+numpy.exp(-z)))

sigma = sigma_fn(z)

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(z, sigma)

ax.set_ylim([-0.1, 1.1])

ax.set_xlim([-5,5])

ax.grid(True)

ax.set_xlabel('z')

ax.set_title('sigmoid function')

plt.show()

"""Step Function"""

z = numpy.arange(-5, 5, .02)

step_fn = numpy.vectorize(lambda z: 1.0 if z >= 0.0 else 0.0)

step = step_fn(z)

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(z, step)

ax.set_ylim([-0.5, 1.5])

ax.set_xlim([-5,5])

ax.grid(True)

ax.set_xlabel('z')

ax.set_title('step function')

plt.show()

"""Sine Function"""

z = numpy.arange(-2*mt.pi, 2*mt.pi, 0.1)

t = numpy.sin(z)

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(z, t)

ax.set_ylim([-1.0, 1.0])

ax.set_xlim([-2*mt.pi,2*mt.pi])

ax.grid(True)

ax.set_xlabel('z')

ax.set_title('sine function')

plt.show()

"""Plots a graph of the squashing function used by a rectified linear

unit"""

z = numpy.arange(-2, 2, .1)

zero = numpy.zeros(len(z))

y = numpy.max([zero, z], axis=0)

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(z, y)

ax.set_ylim([-2.0, 2.0])

ax.set_xlim([-2.0, 2.0])

ax.grid(True)

ax.set_xlabel('z')

ax.set_title('Rectified linear unit')

plt.show()