Week 48: Autoencoders and summary of course#

Morten Hjorth-Jensen, Department of Physics and Center for Computing in Science Education, University of Oslo, Norway

Date: Nov 24, 2025

Copyright 1999-2025, Morten Hjorth-Jensen. Released under CC Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 license

Overview of week 48#

Lecture Monday, November 24#

Plans for the lecture Monday 24 November.

Discussion of Autoencoders and principal component analysis

Summary of course

Readings and Videos#

These lecture notes at CompPhysics/MachineLearning

Video of lecture at https://youtu.be/h2Qa49KlY50

Whiteboard notes at CompPhysics/MachineLearning

Video on Autoencoders at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hZ4a4NgM3u0

Goodfellow et al chapter 14.

Rashcka et al. Their chapter 17 contains a brief introduction only.

Deep Learning Tutorial on AEs from Stanford University at http://ufldl.stanford.edu/tutorial/unsupervised/Autoencoders/

Building AEs in Keras at https://blog.keras.io/building-autoencoders-in-keras.html

Lab sessions#

Lab sessions on Tuesday and Wednesday.

Work on and discussion of project 3.

See updated note on usage of LLMs at the beginning of project description

Last weekly exercise, see exercises week 47 and 48, deadline November 28

Autoencoders: Overarching view#

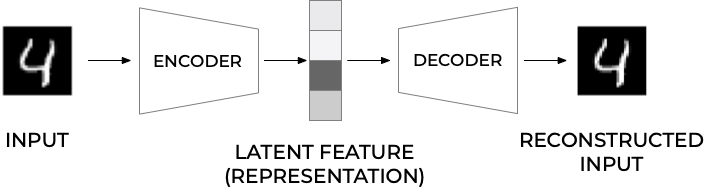

Autoencoders are artificial neural networks capable of learning efficient representations of the input data (these representations are called codings) without any supervision (i.e., the training set is unlabeled). These codings typically have a much lower dimensionality than the input data, making autoencoders useful for dimensionality reduction.

Autoencoders learn to encode the input data into a lower-dimensional representation, and then decode it back to the original data. The goal of autoencoders is to minimize the reconstruction error, which measures how well the output matches the input. Autoencoders can be seen as a way of learning the latent features or hidden structure of the data, and they can be used for data compression, denoising, anomaly detection, and generative modeling.

Powerful detectors#

More importantly, autoencoders act as powerful feature detectors, and they can be used for unsupervised pretraining of deep neural networks.

Lastly, they are capable of randomly generating new data that looks very similar to the training data; this is called a generative model. For example, you could train an autoencoder on pictures of faces, and it would then be able to generate new faces. Surprisingly, autoencoders work by simply learning to copy their inputs to their outputs. This may sound like a trivial task, but we will see that constraining the network in various ways can make it rather difficult. For example, you can limit the size of the internal representation, or you can add noise to the inputs and train the network to recover the original inputs. These constraints prevent the autoencoder from trivially copying the inputs directly to the outputs, which forces it to learn efficient ways of representing the data. In short, the codings are byproducts of the autoencoder’s attempt to learn the identity function under some constraints.

First introduction of AEs#

Autoencoders were first introduced by Rumelhart, Hinton, and Williams in 1986 with the goal of learning to reconstruct the input observations with the lowest error possible.

Why would one want to learn to reconstruct the input observations? If you have problems imagining what that means, think of having a dataset made of images. An autoencoder would be an algorithm that can give as output an image that is as similar as possible to the input one. You may be confused, as there is no apparent reason of doing so. To better understand why autoencoders are useful we need a more informative (although not yet unambiguous) definition.

An autoencoder is a type of algorithm with the primary purpose of learning an “informative” representation of the data that can be used for different applications (see Bank, D., Koenigstein, N., and Giryes, R., Autoencoders) by learning to reconstruct a set of input observations well enough.

Autoencoder structure#

Autoencoders are neural networks where the outputs are its own inputs. They are split into an encoder part which maps the input \(\boldsymbol{x}\) via a function \(f(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{W})\) (this is the encoder part) to a so-called code part (or intermediate part) with the result \(\boldsymbol{h}\)

where \(\boldsymbol{W}\) are the weights to be determined. The decoder parts maps, via its own parameters (weights given by the matrix \(\boldsymbol{V}\) and its own biases) to the final ouput

The goal is to minimize the construction error.

Schematic image of an Autoencoder#

Figure 1:

More on the structure#

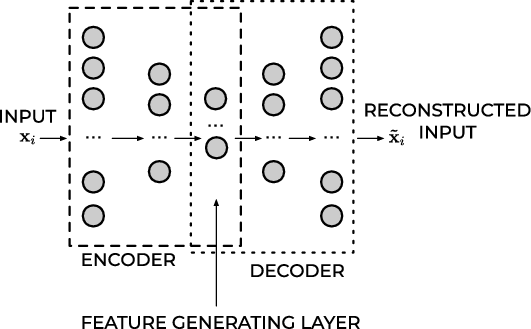

In most typical architectures, the encoder and the decoder are neural networks since they can be easily trained with existing software libraries such as TensorFlow or PyTorch with back propagation.

In general, the encoder can be written as a function \(g\) that will depend on some parameters

where \(\mathbf{h}_{i}\in\mathbb{R}^{q}\) (the latent feature representation) is the output of the encoder block where we evaluate it using the input \(\mathbf{x}_{i}\).

Decoder part#

Note that we have \(g:\mathbb{R}^{n}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^{q}\) The decoder and the output of the network \(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}_{i}\) can be written then as a second generic function of the latent features

where \(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}_{i}\mathbf{\in }\mathbb{R}^{n}\).

Training an autoencoder simply means finding the functions \(g(\cdot)\) and \(f(\cdot)\) that satisfy

Typical AEs#

The standard setup is done via a standard feed forward neural network (FFNN), or what is called a Feed Forward Autoencoder.

A typical FFNN architecture has an odd number of layers and is symmetrical with respect to the middle layer.

Typically, the first layer has a number of neurons \(n_{1} = n\) which equals the size of the input observation \(\mathbf{x}_{\mathbf{i}}\).

As we move toward the center of the network, the number of neurons in each layer drops in some measure. The middle layer usually has the smallest number of neurons. The fact that the number of neurons in this layer is smaller than the size of the input, is often called the bottleneck.

Feed Forward Autoencoder#

Figure 1:

Mirroring#

In almost all practical applications, the layers after the middle one are a mirrored version of the layers before the middle one. For example, an autoencoder with three layers could have the following numbers of neurons:

\(n_{1} = 10\), \(n_{2} = 5\) and then \(n_{3} = n_{1} = 10\) where the input dimension is equal to ten.

All the layers up to and including the middle one, make what is called the encoder, and all the layers from and including the middle one (up to the output) make what is called the decoder.

If the FFNN training is successful, the result will be a good approximation of the input \(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}_{i}\approx\mathbf{x}_{i}\).

What is essential to notice is that the decoder can reconstruct the input by using only a much smaller number of features than the input observations initially have.

Output of middle layer#

The output of the middle layer \(\mathbf{h}_{\mathbf{i}}\) are also called a learned representation of the input observation \(\mathbf{x}_{i}\).

The encoder can reduce the number of dimensions of the input observation and create a learned representation of the input that has a smaller dimension \(q<n\).

This learned representation is enough for the decoder to reconstruct the input accurately (if the autoencoder training was successful as intended).

Activation Function of the Output Layer#

In autoencoders based on neural networks, the output layer’s activation function plays a particularly important role. The most used functions are ReLU and Sigmoid.

ReLU#

The ReLU activation function can assume all values in the range \(\left[0,\infty\right]\). As a remainder, its formula is

This choice is good when the input observations (\mathbf{x}_{i}) assume a wide range of positive values. If the input \(\mathbf{x}_{i}\) can assume negative values, the ReLU is, of course, a terrible choice, and the identity function is a much better choice. It is then common to replace to the ReLU with the so-called Leaky ReLu or just modified ReLU.

The ReLU activation function for the output layer is well suited for cases when the input observations (\mathbf{x}_{i}) assume a wide range of positive real values.

Sigmoid#

The sigmoid function \(\sigma\) can assume all values in the range \([0,1]\),

This activation function can only be used if the input observations \(\mathbf{x}_{i}\) are all in the range \([0,1]\) or if you have normalized them to be in that range. Consider as an example the MNIST dataset. Each value of the input observation \(\mathbf{x}_{i}\) (one image) is the gray values of the pixels that can assume any value from 0 to 255. Normalizing the data by dividing the pixel values by 255 would make each observation (each image) have only pixel values between 0 and 1. In this case, the sigmoid would be a good choice for the output layer’s activation function.

Cost/Loss Function#

If an autoencoder is trying to solve a regression problem, the most common choice as a loss function is the Mean Square Error

Binary Cross-Entropy#

If the activation function of the output layer of the AE is a sigmoid function, thus limiting neuron outputs to be between 0 and 1, and the input features are normalized to be between 0 and 1 we can use as loss function the binary cross-entropy. This cots/loss function is typically used in classification problems, but it works well for autoencoders. The formula for it is

Reconstruction Error#

The reconstruction error (RE) is a metric that gives you an indication of how good (or bad) the autoencoder was able to reconstruct the input observation \(\mathbf{x}_{i}\). The most typical RE used is the MSE

Temporary summary on Autoencoders#

Understand the basic autoencoder architecture (encoder, latent space, decoder).

Understand the linear autoencoder and its connection to PCA. Good for understanding; nonlinear AE (with activations) can learn more complex manifolds.

What is an Autoencoder? An autoencoder (AE) is a neural network trained to reconstruct its input: \(\hat{x}=\mathrm{Dec}(\mathrm{Enc}(x))\).

Components:

\textbf{Encoder} \(f_\theta:\mathbb{R}^d\to\mathbb{R}^m\) compresses input to latent code \(h=f_\theta(x)\)

\textbf{Decoder} \(g_\phi:\mathbb{R}^m\to\mathbb{R}^d\) reconstructs \(\hat{x}=g_\phi(h)\)

Training objective: minimize reconstruction loss, e.g. MSE \mathcal{L}(\theta,\phi)=\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N |x^{(i)}-g_\phi(f_\theta(x^{(i)}))|^2_2.

Linear autoencoders and the PCA theorem#

The covariance matrix is given as

Let us now assume that we can perform a series of orthogonal transformations where we employ some orthogonal matrices \(\boldsymbol{S}\). These matrices are defined as \(\boldsymbol{S}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{p\times p}\) and obey the orthogonality requirements \(\boldsymbol{S}\boldsymbol{S}^T=\boldsymbol{S}^T\boldsymbol{S}=\boldsymbol{I}\). The matrix can be written out in terms of the column vectors \(\boldsymbol{s}_i\) as \(\boldsymbol{S}=[\boldsymbol{s}_0,\boldsymbol{s}_1,\dots,\boldsymbol{s}_{p-1}]\) and \(\boldsymbol{s}_i \in {\mathbb{R}}^{p}\).

More details#

Assume also that there is a transformation \(\boldsymbol{S}^T\boldsymbol{C}[\boldsymbol{x}]\boldsymbol{S}=\boldsymbol{C}[\boldsymbol{y}]\) such that the new matrix \(\boldsymbol{C}[\boldsymbol{y}]\) is diagonal with elements \([\lambda_0,\lambda_1,\lambda_2,\dots,\lambda_{p-1}]\).

That is we have

since the matrix \(\boldsymbol{S}\) is not a data dependent matrix. Multiplying with \(\boldsymbol{S}\) from the left we have

and since \(\boldsymbol{C}[\boldsymbol{y}]\) is diagonal we have for a given eigenvalue \(i\) of the covariance matrix that

The PCA Theorem#

In the derivation of the PCA theorem we will assume that the eigenvalues are ordered in descending order, that is \(\lambda_0 > \lambda_1 > \dots > \lambda_{p-1}\).

The eigenvalues tell us then how much we need to stretch the corresponding eigenvectors. Dimensions with large eigenvalues have thus large variations (large variance) and define therefore useful dimensions. The data points are more spread out in the direction of these eigenvectors. Smaller eigenvalues mean on the other hand that the corresponding eigenvectors are shrunk accordingly and the data points are tightly bunched together and there is not much variation in these specific directions. Hopefully then we could leave it out dimensions where the eigenvalues are very small. If \(p\) is very large, we could then aim at reducing \(p\) to \(l << p\) and handle only \(l\) features/predictors.

The Algorithm before theorem#

Here’s how we would proceed in setting up the algorithm for the PCA, see also discussion below here. Set up the datapoints for the design/feature matrix \(\boldsymbol{X}\) with \(\boldsymbol{X}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{n\times p}\), with the predictors/features \(p\) referring to the column numbers and the entries \(n\) being the row elements.

Further steps#

Center the data by subtracting the mean value for each column. This leads to a new matrix \(\boldsymbol{X}\rightarrow \overline{\boldsymbol{X}}\).

Compute then the covariance/correlation matrix \(\mathbb{E}[\overline{\boldsymbol{X}}^T\overline{\boldsymbol{X}}]\).

Find the eigenpairs of \(\boldsymbol{C}\) with eigenvalues \([\lambda_0,\lambda_1,\dots,\lambda_{p-1}]\) and eigenvectors \([\boldsymbol{s}_0,\boldsymbol{s}_1,\dots,\boldsymbol{s}_{p-1}]\).

Order the eigenvalue (and the eigenvectors accordingly) in order of decreasing eigenvalues.

Keep only those \(l\) eigenvalues larger than a selected threshold value, discarding thus \(p-l\) features since we expect small variations in the data here.

Writing our own PCA code#

We will use a simple example first with two-dimensional data drawn from a multivariate normal distribution with the following mean and covariance matrix (we have fixed these quantities but will play around with them below):

Note that the mean refers to each column of data. We will generate \(n = 10000\) points \(X = \{ x_1, \ldots, x_N \}\) from this distribution, and store them in the \(1000 \times 2\) matrix \(\boldsymbol{X}\). This is our design matrix where we have forced the covariance and mean values to take specific values.

Implementing it#

The following Python code aids in setting up the data and writing out the design matrix. Note that the function multivariate returns also the covariance discussed above and that it is defined by dividing by \(n-1\) instead of \(n\).

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from IPython.display import display

n = 10000

mean = (-1, 2)

cov = [[4, 2], [2, 2]]

X = np.random.multivariate_normal(mean, cov, n)

Now we are going to implement the PCA algorithm. We will break it down into various substeps.

First Step#

The first step of PCA is to compute the sample mean of the data and use it to center the data. Recall that the sample mean is

and the mean-centered data \(\bar{X} = \{ \bar{x}_1, \ldots, \bar{x}_n \}\) takes the form

When you are done with these steps, print out \(\mu_n\) to verify it is close to \(\mu\) and plot your mean centered data to verify it is centered at the origin! The following code elements perform these operations using pandas or using our own functionality for doing so. The latter, using numpy is rather simple through the mean() function.

df = pd.DataFrame(X)

# Pandas does the centering for us

df = df -df.mean()

# we center it ourselves

X_centered = X - X.mean(axis=0)

Scaling#

Alternatively, we could use the functions we discussed earlier for scaling the data set. That is, we could have used the StandardScaler function in Scikit-Learn, a function which ensures that for each feature/predictor we study the mean value is zero and the variance is one (every column in the design/feature matrix). You would then not get the same results, since we divide by the variance. The diagonal covariance matrix elements will then be one, while the non-diagonal ones need to be divided by \(2\sqrt{2}\) for our specific case.

Centered Data#

Now we are going to use the mean centered data to compute the sample covariance of the data by using the following equation

where the data points \(x_i \in \mathbb{R}^p\) (here in this example \(p = 2\)) are column vectors and \(x^T\) is the transpose of \(x\). We can write our own code or simply use either the functionaly of numpy or that of pandas, as follows

print(df.cov())

print(np.cov(X_centered.T))

Note that the way we define the covariance matrix here has a factor \(n-1\) instead of \(n\). This is included in the cov() function by numpy and pandas. Our own code here is not very elegant and asks for obvious improvements. It is tailored to this specific \(2\times 2\) covariance matrix.

# extract the relevant columns from the centered design matrix of dim n x 2

x = X_centered[:,0]

y = X_centered[:,1]

Cov = np.zeros((2,2))

Cov[0,1] = np.sum(x.T@y)/(n-1.0)

Cov[0,0] = np.sum(x.T@x)/(n-1.0)

Cov[1,1] = np.sum(y.T@y)/(n-1.0)

Cov[1,0]= Cov[0,1]

print("Centered covariance using own code")

print(Cov)

plt.plot(x, y, 'x')

plt.axis('equal')

plt.show()

Exploring#

Depending on the number of points \(n\), we will get results that are close to the covariance values defined above. The plot shows how the data are clustered around a line with slope close to one. Is this expected? Try to change the covariance and the mean values. For example, try to make the variance of the first element much larger than that of the second diagonal element. Try also to shrink the covariance (the non-diagonal elements) and see how the data points are distributed.

Diagonalize the sample covariance matrix to obtain the principal components#

Now we are ready to solve for the principal components! To do so we diagonalize the sample covariance matrix \(\Sigma\). We can use the function np.linalg.eig to do so. It will return the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of \(\Sigma\). Once we have these we can perform the following tasks:

We compute the percentage of the total variance captured by the first principal component

We plot the mean centered data and lines along the first and second principal components

Then we project the mean centered data onto the first and second principal components, and plot the projected data.

Finally, we approximate the data as

where \(v_0\) is the first principal component.

Collecting all Steps#

Collecting all these steps we can write our own PCA function and compare this with the functionality included in Scikit-Learn.

The code here outlines some of the elements we could include in the analysis. Feel free to extend upon this in order to address the above questions.

# diagonalize and obtain eigenvalues, not necessarily sorted

EigValues, EigVectors = np.linalg.eig(Cov)

# sort eigenvectors and eigenvalues

#permute = EigValues.argsort()

#EigValues = EigValues[permute]

#EigVectors = EigVectors[:,permute]

print("Eigenvalues of Covariance matrix")

for i in range(2):

print(EigValues[i])

FirstEigvector = EigVectors[:,0]

SecondEigvector = EigVectors[:,1]

print("First eigenvector")

print(FirstEigvector)

print("Second eigenvector")

print(SecondEigvector)

#thereafter we do a PCA with Scikit-learn

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

pca = PCA(n_components = 2)

X2Dsl = pca.fit_transform(X)

print("Eigenvector of largest eigenvalue")

print(pca.components_.T[:, 0])

This code does not contain all the above elements, but it shows how we can use Scikit-Learn to extract the eigenvector which corresponds to the largest eigenvalue. Try to address the questions we pose before the above code. Try also to change the values of the covariance matrix by making one of the diagonal elements much larger than the other. What do you observe then?

Classical PCA Theorem#

We assume now that we have a design matrix \(\boldsymbol{X}\) which has been centered as discussed above. For the sake of simplicity we skip the overline symbol. The matrix is defined in terms of the various column vectors \([\boldsymbol{x}_0,\boldsymbol{x}_1,\dots, \boldsymbol{x}_{p-1}]\) each with dimension \(\boldsymbol{x}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{n}\).

The PCA theorem states that minimizing the above reconstruction error corresponds to setting \(\boldsymbol{W}=\boldsymbol{S}\), the orthogonal matrix which diagonalizes the empirical covariance(correlation) matrix. The optimal low-dimensional encoding of the data is then given by a set of vectors \(\boldsymbol{z}_i\) with at most \(l\) vectors, with \(l << p\), defined by the orthogonal projection of the data onto the columns spanned by the eigenvectors of the covariance(correlations matrix).

The PCA Theorem#

To show the PCA theorem let us start with the assumption that there is one vector \(\boldsymbol{s}_0\) which corresponds to a solution which minimized the reconstruction error \(J\). This is an orthogonal vector. It means that we now approximate the reconstruction error in terms of \(\boldsymbol{w}_0\) and \(\boldsymbol{z}_0\) as

We are almost there, we have obtained a relation between minimizing the reconstruction error and the variance and the covariance matrix. Minimizing the error is equivalent to maximizing the variance of the projected data.

We could trivially maximize the variance of the projection (and thereby minimize the error in the reconstruction function) by letting the norm-2 of \(\boldsymbol{w}_0\) go to infinity. However, this norm since we want the matrix \(\boldsymbol{W}\) to be an orthogonal matrix, is constrained by \(\vert\vert \boldsymbol{w}_0 \vert\vert_2^2=1\). Imposing this condition via a Lagrange multiplier we can then in turn maximize

Taking the derivative with respect to \(\boldsymbol{w}_0\) we obtain

meaning that

The direction that maximizes the variance (or minimizes the construction error) is an eigenvector of the covariance matrix! If we left multiply with \(\boldsymbol{w}_0^T\) we have the variance of the projected data is

If we want to maximize the variance (minimize the construction error) we simply pick the eigenvector of the covariance matrix with the largest eigenvalue. This establishes the link between the minimization of the reconstruction function \(J\) in terms of an orthogonal matrix and the maximization of the variance and thereby the covariance of our observations encoded in the design/feature matrix \(\boldsymbol{X}\).

The proof for the other eigenvectors \(\boldsymbol{w}_1,\boldsymbol{w}_2,\dots\) can be established by applying the above arguments and using the fact that our basis of eigenvectors is orthogonal, see Murphy chapter 12.2. The discussion in chapter 12.2 of Murphy’s text has also a nice link with the Singular Value Decomposition theorem. For categorical data, see chapter 12.4 and discussion therein.

For more details, see for example Vidal, Ma and Sastry, chapter 2.

Geometric Interpretation and link with Singular Value Decomposition#

For a detailed demonstration of the geometric interpretation, see Vidal, Ma and Sastry, section 2.1.2.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is by far the most popular dimensionality reduction algorithm. First it identifies the hyperplane that lies closest to the data, and then it projects the data onto it.

The following Python code uses NumPy’s svd() function to obtain all the principal components of the training set, then extracts the first two principal components. First we center the data using either pandas or our own code

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from IPython.display import display

np.random.seed(100)

# setting up a 10 x 5 vanilla matrix

rows = 10

cols = 5

X = np.random.randn(rows,cols)

df = pd.DataFrame(X)

# Pandas does the centering for us

df = df -df.mean()

display(df)

# we center it ourselves

X_centered = X - X.mean(axis=0)

# Then check the difference between pandas and our own set up

print(X_centered-df)

#Now we do an SVD

U, s, V = np.linalg.svd(X_centered)

c1 = V.T[:, 0]

c2 = V.T[:, 1]

W2 = V.T[:, :2]

X2D = X_centered.dot(W2)

print(X2D)

PCA assumes that the dataset is centered around the origin. Scikit-Learn’s PCA classes take care of centering the data for you. However, if you implement PCA yourself (as in the preceding example), or if you use other libraries, don’t forget to center the data first.

Once you have identified all the principal components, you can reduce the dimensionality of the dataset down to \(d\) dimensions by projecting it onto the hyperplane defined by the first \(d\) principal components. Selecting this hyperplane ensures that the projection will preserve as much variance as possible.

W2 = V.T[:, :2]

X2D = X_centered.dot(W2)

PCA and scikit-learn#

Scikit-Learn’s PCA class implements PCA using SVD decomposition just like we did before. The following code applies PCA to reduce the dimensionality of the dataset down to two dimensions (note that it automatically takes care of centering the data):

#thereafter we do a PCA with Scikit-learn

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

pca = PCA(n_components = 2)

X2D = pca.fit_transform(X)

print(X2D)

After fitting the PCA transformer to the dataset, you can access the principal components using the components variable (note that it contains the PCs as horizontal vectors, so, for example, the first principal component is equal to

pca.components_.T[:, 0]

Another very useful piece of information is the explained variance ratio of each principal component, available via the \(explained\_variance\_ratio\) variable. It indicates the proportion of the dataset’s variance that lies along the axis of each principal component.

Example of Cancer Data#

We can now repeat the above but applied to real data, in this case the Wisconsin breast cancer data. Here we compute performance scores on the training data using logistic regression.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

cancer = load_breast_cancer()

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(cancer.data,cancer.target,random_state=0)

logreg = LogisticRegression()

logreg.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("Train set accuracy from Logistic Regression: {:.2f}".format(logreg.score(X_train,y_train)))

# We scale the data

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

scaler = StandardScaler()

scaler.fit(X_train)

X_train_scaled = scaler.transform(X_train)

X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test)

# Then perform again a log reg fit

logreg.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train)

print("Train set accuracy scaled data: {:.2f}".format(logreg.score(X_train_scaled,y_train)))

#thereafter we do a PCA with Scikit-learn

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

pca = PCA(n_components = 2)

X2D_train = pca.fit_transform(X_train_scaled)

# and finally compute the log reg fit and the score on the training data

logreg.fit(X2D_train,y_train)

print("Train set accuracy scaled and PCA data: {:.2f}".format(logreg.score(X2D_train,y_train)))

We see that our training data after the PCA decomposition has a performance similar to the non-scaled data.

Instead of arbitrarily choosing the number of dimensions to reduce down to, it is generally preferable to choose the number of dimensions that add up to a sufficiently large portion of the variance (e.g., 95%). Unless, of course, you are reducing dimensionality for data visualization — in that case you will generally want to reduce the dimensionality down to 2 or 3. The following code computes PCA without reducing dimensionality, then computes the minimum number of dimensions required to preserve 95% of the training set’s variance:

pca = PCA()

pca.fit(X_train)

cumsum = np.cumsum(pca.explained_variance_ratio_)

d = np.argmax(cumsum >= 0.95) + 1

You could then set \(n\_components=d\) and run PCA again. However, there is a much better option: instead of specifying the number of principal components you want to preserve, you can set \(n\_components\) to be a float between 0.0 and 1.0, indicating the ratio of variance you wish to preserve:

pca = PCA(n_components=0.95)

X_reduced = pca.fit_transform(X_train)

Incremental PCA#

One problem with the preceding implementation of PCA is that it requires the whole training set to fit in memory in order for the SVD algorithm to run. Fortunately, Incremental PCA (IPCA) algorithms have been developed: you can split the training set into mini-batches and feed an IPCA algorithm one minibatch at a time. This is useful for large training sets, and also to apply PCA online (i.e., on the fly, as new instances arrive).

Randomized PCA#

Scikit-Learn offers yet another option to perform PCA, called Randomized PCA. This is a stochastic algorithm that quickly finds an approximation of the first d principal components. Its computational complexity is \(O(m \times d^2)+O(d^3)\), instead of \(O(m \times n^2) + O(n^3)\), so it is dramatically faster than the previous algorithms when \(d\) is much smaller than \(n\).

Kernel PCA#

The kernel trick is a mathematical technique that implicitly maps instances into a very high-dimensional space (called the feature space), enabling nonlinear classification and regression with Support Vector Machines. Recall that a linear decision boundary in the high-dimensional feature space corresponds to a complex nonlinear decision boundary in the original space. It turns out that the same trick can be applied to PCA, making it possible to perform complex nonlinear projections for dimensionality reduction. This is called Kernel PCA (kPCA). It is often good at preserving clusters of instances after projection, or sometimes even unrolling datasets that lie close to a twisted manifold. For example, the following code uses Scikit-Learn’s KernelPCA class to perform kPCA with an

from sklearn.decomposition import KernelPCA

rbf_pca = KernelPCA(n_components = 2, kernel="rbf", gamma=0.04)

X_reduced = rbf_pca.fit_transform(X)

Other techniques#

There are many other dimensionality reduction techniques, several of which are available in Scikit-Learn.

Here are some of the most popular:

Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) reduces dimensionality while trying to preserve the distances between the instances.

Isomap creates a graph by connecting each instance to its nearest neighbors, then reduces dimensionality while trying to preserve the geodesic distances between the instances.

t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) reduces dimensionality while trying to keep similar instances close and dissimilar instances apart. It is mostly used for visualization, in particular to visualize clusters of instances in high-dimensional space (e.g., to visualize the MNIST images in 2D).

Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) is actually a classification algorithm, but during training it learns the most discriminative axes between the classes, and these axes can then be used to define a hyperplane onto which to project the data. The benefit is that the projection will keep classes as far apart as possible, so LDA is a good technique to reduce dimensionality before running another classification algorithm such as a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier discussed in the SVM lectures.

Back to Autoencoders: Linear Autoencoders#

PyTorch example#

We will, again, use the MNIST database, which has \(60000\) training examples and a test set of 10000 handwritten numbers. The images have only one color channel and have a size of \(28\times 28\) pixels. We start by uploading the data set.

# import the Torch packages

# transforms are used to preprocess the images, e.g. crop, rotate, normalize, etc

import torch

from torchvision import datasets,transforms

# specify the data path in which you would like to store the downloaded files

# ToTensor() here is used to convert data type to tensor

train_dataset = datasets.MNIST(root='./mnist_data/', train=True, transform=transforms.ToTensor(), download=True)

test_dataset = datasets.MNIST(root='./mnist_data/', train=False, transform=transforms.ToTensor(), download=True)

print(train_dataset)

batchSize=128

#only after packed in DataLoader, can we feed the data into the neural network iteratively

train_loader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(dataset=train_dataset, batch_size=batchSize, shuffle=True)

test_loader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(dataset=test_dataset, batch_size=batchSize, shuffle=False)

We visualize the images here using the \(imshow\) function function and the \(make\_grid\) function from PyTorch to arrange and display them.

# package we used to manipulate matrix

import numpy as np

# package we used for image processing

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

from torchvision.utils import make_grid

def imshow(img):

npimg = img.numpy()

#transpose: change array axis to correspond to the plt.imshow() function

plt.imshow(np.transpose(npimg, (1, 2, 0)))

plt.show()

# load the first 16 training samples from next iteration

# [:16,:,:,:] for the 4 dimension of examples, first dimension take first 16, other dimension take all data

# arrange the image in grid

examples, _ = next(iter(train_loader))

example_show=make_grid(examples[:16,:,:,:], 4)

# then display them

imshow(example_show)

Our autoencoder consists of two parts, see also the TensorFlow example above. The encoder and decoder parts are represented by two fully connected feed forward neural networks where we use the standard Sigmoid function. In the encoder part we reduce the dimensionality of the image from \(28\times 28=784\) pixels to first \(16\times 16=256\) pixels and then to 128 pixels. The 128 pixel representation is then used to define the representation of the input and the input to the decoder part. The latter attempts to reconstruct the images.

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

import torch.optim as optim

# Network Parameters

num_hidden_1 = 256 # 1st layer num features

num_hidden_2 = 128 # 2nd layer num features (the latent dim)

num_input = 784 # MNIST data input (img shape: 28*28)

# Building the encoder

class Autoencoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, x_dim, h_dim1, h_dim2):

super(Autoencoder, self).__init__()

# encoder part

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(x_dim, h_dim1)

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(h_dim1, h_dim2)

# decoder part

self.fc3 = nn.Linear(h_dim2, h_dim1)

self.fc4 = nn.Linear(h_dim1, x_dim)

def encoder(self, x):

x = torch.sigmoid(self.fc1(x))

x = torch.sigmoid(self.fc2(x))

return x

def decoder(self, x):

x = torch.sigmoid(self.fc3(x))

x = torch.sigmoid(self.fc4(x))

return x

def forward(self, x):

x = self.encoder(x)

x = self.decoder(x)

return x

# When initializing, it will run __init__() function as above

model = Autoencoder(num_input, num_hidden_1, num_hidden_2)

We define here the cost/loss function and the optimizer we employ (Adam here).

# define loss function and parameters

optimizer = optim.Adam(model.parameters())

epoch = 100

# MSE loss will calculate Mean Squared Error between the inputs

loss_function = nn.MSELoss()

print('====Training start====')

for i in range(epoch):

train_loss = 0

for batch_idx, (data, _) in enumerate(train_loader):

# prepare input data

inputs = torch.reshape(data,(-1, 784)) # -1 can be any value.

# set gradient to zero

optimizer.zero_grad()

# feed inputs into model

recon_x = model(inputs)

# calculating loss

loss = loss_function(recon_x, inputs)

# calculate gradient of each parameter

loss.backward()

train_loss += loss.item()

# update the weight based on the gradient calculated

optimizer.step()

if i%10==0:

print('====> Epoch: {} Average loss: {:.9f}'.format(i, train_loss ))

print('====Training finish====')

As we have trained the network, we will now reconstruct various test samples to see if the model can generalize to data which were not included in the training set.

# load 16 images from testset

inputs, _ = next(iter(test_loader))

inputs_example = make_grid(inputs[:16,:,:,:],4)

imshow(inputs_example)

#convert from image to tensor

#inputs=inputs.cuda()

inputs=torch.reshape(inputs,(-1,784))

# get the outputs from the trained model

outputs=model(inputs)

#convert from tensor to image

outputs=torch.reshape(outputs,(-1,1,28,28))

outputs=outputs.detach().cpu()

#show the output images

outputs_example = make_grid(outputs[:16,:,:,:],4)

imshow(outputs_example)

After training the auto-encoder, we can now use the model to reconstruct some images. In order to reconstruct different training images, the model has learned to recognize how the image looks like and describe it in the 128-dimensional latent space. In other words, the visual information of images is compressed and encoded in the 128-dimensional representations. As we assume that samples from the same categories should be more visually similar than those from different classes, the representations can then be used for image recognition, i.e., handwritten digit images recognition in our case.

One simple way to recognize images is to randomly select ten training samples from each class and annotate them with the corresponding label. Then given the test data, we can predict which classes they belong to by finding the most similar labelled training samples to them.

# get 100 image-label pairs from training set

x_train, y_train = next(iter(train_loader))

# 10 classes, 10 samples per class, 100 in total

candidates = np.random.choice(batchSize, 10*10)

# randomly select 100 samples

x_train = x_train[candidates]

y_train = y_train[candidates]

# display the selected samples and print their labels

imshow(make_grid(x_train[:100,:,:,:],10))

print(y_train.reshape(10, 10))

# get 100 image-label pairs from test set

x_test, y_test = next(iter(train_loader))

candidates_test = np.random.choice(batchSize, 10*10)

x_test = x_test[candidates_test]

y_test = y_test[candidates_test]

# display the selected samples and print their labels

imshow(make_grid(x_test[:100,:,:,:],10))

print(y_test.reshape(10, 10))

# compute the representations of training and test samples

#h_train=model.encoder(torch.reshape(x_train.cuda(),(-1,784)))

#h_test=model.encoder(torch.reshape(x_test.cuda(),(-1,784)))

h_train=model.encoder(torch.reshape(x_train,(-1,784)))

h_test=model.encoder(torch.reshape(x_test,(-1,784)))

# find the nearest training samples to each test instance, in terms of MSE

MSEs = np.mean(np.power(np.expand_dims(h_test.detach().cpu(), axis=1) - np.expand_dims(h_train.detach().cpu(), axis=0), 2), axis=2)

neighbours = MSEs.argmin(axis=1)

predicts = y_train[neighbours]

# print(np.stack([y_test, predicts], axis=1))

print('Recognition accuracy according to the learned representation is %.1f%%' % (100 * (y_test == predicts).numpy().astype(np.float32).mean()))

Summary of course#

What? Me worry? No final exam in this course!#

Figure 1:

Topics we have covered this year#

The course has two central parts

Statistical analysis and optimization of data

Machine learning

Statistical analysis and optimization of data#

The following topics have been discussed:

Basic concepts, expectation values, variance, covariance, correlation functions and errors;

Simpler models, binomial distribution, the Poisson distribution, simple and multivariate normal distributions;

Central elements from linear algebra, matrix inversion and SVD

Gradient methods for data optimization

Estimation of errors using cross-validation, bootstrapping and jackknife methods;

Practical optimization using Singular-value decomposition and least squares for parameterizing data.

Not discussed: Principal Component Analysis to reduce the number of features.

Machine learning#

Linear methods for regression and classification:

a. Ordinary Least Squares

b. Ridge regression

c. Lasso regression

d. Logistic regression

Neural networks and deep learning:

a. Feed Forward Neural Networks

b. Convolutional Neural Networks

c. Recurrent Neural Networks

d. Autoencoders and PCA

Not discussed this year Decisions trees and ensemble methods:

a. Decision trees

b. Bagging and voting

c. Random forests

d. Boosting and gradient boosting

Not discussed this year: Support vector machines

a. Binary classification and multiclass classification

b. Kernel methods

c. Regression

Learning outcomes and overarching aims of this course#

The course introduces a variety of central algorithms and methods essential for studies of data analysis and machine learning. The course is project based and through the various projects, normally three, you will be exposed to fundamental research problems in these fields, with the aim to reproduce state of the art scientific results. The students will learn to develop and structure large codes for studying these systems, get acquainted with computing facilities and learn to handle large scientific projects. A good scientific and ethical conduct is emphasized throughout the course.

Understand linear methods for regression and classification;

Learn about neural network and deep learning methods;

Learn about basic data analysis;

Be capable of extending the acquired knowledge to other systems and cases;

Have an understanding of central algorithms used in data analysis and machine learning;

Work on numerical projects to illustrate the theory. The projects play a central role.

Perspective on Machine Learning#

Rapidly emerging application area

Experiment AND theory are evolving in many many fields.

Requires education/retraining for more widespread adoption

A lot of “word-of-mouth” development methods

And LLMs are playing a big role here

Huge amounts of data sets require automation, classical analysis tools often inadequate. High energy physics hit this wall in the 90’s. In 2009 single top quark production was determined via Boosted decision trees, Bayesian Neural Networks, etc.

Machine Learning Research#

Where to find recent results:

Conference proceedings, arXiv and blog posts!

ICML: International Conference on Machine Learning

Starting your Machine Learning Project#

Identify problem type: classification, regression

Consider your data carefully

Choose a simple model that fits 1 and 2

Consider your data carefully again! Think of data representation more carefully.

Based on your results, feedback loop to earliest possible point

Choose a Model and Algorithm#

Supervised?

Start with the simplest model that fits your problem

Start with minimal processing of data

Preparing Your Data#

Shuffle your data

Mean center your data

Why?

Normalize the variance

Why?

Whitening

Decorrelates data

Can be hit or miss

When to do train/test split?

Which activation and weights to choose in neural networks#

RELU? ELU? GELU? etc

Sigmoid or Tanh?

Set all weights to 0? Terrible idea

Set all weights to random values? Small random values

Optimization Methods and Hyperparameters#

Stochastic gradient descent

Stochastic gradient descent + momentum

State-of-the-art approaches:

a. RMSProp

b. Adam

c. and more

Which regularization and hyperparameters? \(L_1\) or \(L_2\), soft classifiers, depths of trees and many other. Need to explore a large set of hyperparameters and regularization methods.

Resampling#

When do we resample?

Jackknife and many other

Other courses on Data science and Machine Learning at UiO#

FYS5429 – Advanced machine learning and data analysis for the physical sciences

IN3050/IN4050 Introduction to Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. Introductory course in machine learning and AI

STK-INF3000/4000 Selected Topics in Data Science. The course provides insight into selected contemporary relevant topics within Data Science.

IN4080 Natural Language Processing. Probabilistic and machine learning techniques applied to natural language processing.

STK-IN4300 – Statistical learning methods in Data Science. An advanced introduction to statistical and machine learning. For students with a good mathematics and statistics background.

IN-STK5000 Responsible Data Science. Methods for adaptive collection and processing of data based on machine learning techniques.

IN4310 – Machine Learning for Image Analysis. An introduction to deep learning with particular emphasis on applications within Image analysis, but useful for other application areas too.

IN5490 – Advanced Topics in Artificial Intelligence for Intelligent Systems

TEK5040 – Deep learning for autonomous systems. The course addresses advanced algorithms and architectures for deep learning with neural networks. The course provides an introduction to how deep-learning techniques can be used in the construction of key parts of advanced autonomous systems that exist in physical environments and cyber environments.

Additional courses of interest#

What’s the future like?#

Based on multi-layer nonlinear neural networks, deep learning can learn directly from raw data, automatically extract and abstract features from layer to layer, and then achieve the goal of regression, classification, or ranking. Deep learning has made breakthroughs in computer vision, speech processing and natural language, and reached or even surpassed human level. The success of deep learning is mainly due to the three factors: big data, big model, and big computing.

In the past few decades, many different architectures of deep neural networks have been proposed, such as

Convolutional neural networks, which are mostly used in image and video data processing, and have also been applied to sequential data such as text processing;

Recurrent neural networks, which can process sequential data of variable length and have been widely used in natural language understanding and speech processing;

Encoder-decoder framework, which is mostly used for image or sequence generation, such as machine translation, text summarization, and image captioning.

Types of Machine Learning, a repetition#

The approaches to machine learning are many, but are often split into two main categories. In supervised learning we know the answer to a problem, and let the computer deduce the logic behind it. On the other hand, unsupervised learning is a method for finding patterns and relationship in data sets without any prior knowledge of the system. Some authours also operate with a third category, namely reinforcement learning. This is a paradigm of learning inspired by behavioural psychology, where learning is achieved by trial-and-error, solely from rewards and punishment.

Another way to categorize machine learning tasks is to consider the desired output of a system. Some of the most common tasks are:

Classification: Outputs are divided into two or more classes. The goal is to produce a model that assigns inputs into one of these classes. An example is to identify digits based on pictures of hand-written ones. Classification is typically supervised learning.

Regression: Finding a functional relationship between an input data set and a reference data set. The goal is to construct a function that maps input data to continuous output values.

Clustering: Data are divided into groups with certain common traits, without knowing the different groups beforehand. It is thus a form of unsupervised learning.

Other unsupervised learning algortihms like Boltzmann machines

Why Boltzmann machines?#

What is known as restricted Boltzmann Machines (RMB) have received a lot of attention lately. One of the major reasons is that they can be stacked layer-wise to build deep neural networks that capture complicated statistics.

The original RBMs had just one visible layer and a hidden layer, but recently so-called Gaussian-binary RBMs have gained quite some popularity in imaging since they are capable of modeling continuous data that are common to natural images.

Furthermore, they have been used to solve complicated quantum mechanical many-particle problems or classical statistical physics problems like the Ising and Potts classes of models.

Boltzmann Machines#

Why use a generative model rather than the more well known discriminative deep neural networks (DNN)?

Discriminitave methods have several limitations: They are mainly supervised learning methods, thus requiring labeled data. And there are tasks they cannot accomplish, like drawing new examples from an unknown probability distribution.

A generative model can learn to represent and sample from a probability distribution. The core idea is to learn a parametric model of the probability distribution from which the training data was drawn. As an example

a. A model for images could learn to draw new examples of cats and dogs, given a training dataset of images of cats and dogs.

b. Generate a sample of an ordered or disordered phase, having been given samples of such phases.

c. Model the trial function for Monte Carlo calculations.

Some similarities and differences from DNNs#

Both use gradient-descent based learning procedures for minimizing cost functions

Energy based models don’t use backpropagation and automatic differentiation for computing gradients, instead turning to Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods.

DNNs often have several hidden layers. A restricted Boltzmann machine has only one hidden layer, however several RBMs can be stacked to make up Deep Belief Networks, of which they constitute the building blocks.

History: The RBM was developed by amongst others Geoffrey Hinton, called by some the “Godfather of Deep Learning”, working with the University of Toronto and Google.

Boltzmann machines (BM)#

A BM is what we would call an undirected probabilistic graphical model with stochastic continuous or discrete units.

It is interpreted as a stochastic recurrent neural network where the state of each unit(neurons/nodes) depends on the units it is connected to. The weights in the network represent thus the strength of the interaction between various units/nodes.

It turns into a Hopfield network if we choose deterministic rather than stochastic units. In contrast to a Hopfield network, a BM is a so-called generative model. It allows us to generate new samples from the learned distribution.

A standard BM setup#

A standard BM network is divided into a set of observable and visible units \(\hat{x}\) and a set of unknown hidden units/nodes \(\hat{h}\).

Additionally there can be bias nodes for the hidden and visible layers. These biases are normally set to \(1\).

BMs are stackable, meaning they cwe can train a BM which serves as input to another BM. We can construct deep networks for learning complex PDFs. The layers can be trained one after another, a feature which makes them popular in deep learning

However, they are often hard to train. This leads to the introduction of so-called restricted BMs, or RBMS. Here we take away all lateral connections between nodes in the visible layer as well as connections between nodes in the hidden layer. The network is illustrated in the figure below.

The structure of the RBM network#

Figure 1:

The network#

The network layers:

A function \(\mathbf{x}\) that represents the visible layer, a vector of \(M\) elements (nodes). This layer represents both what the RBM might be given as training input, and what we want it to be able to reconstruct. This might for example be given by the pixels of an image or coefficients representing speech, or the coordinates of a quantum mechanical state function.

The function \(\mathbf{h}\) represents the hidden, or latent, layer. A vector of \(N\) elements (nodes). Also called “feature detectors”.

Goals#

The goal of the hidden layer is to increase the model’s expressive power. We encode complex interactions between visible variables by introducing additional, hidden variables that interact with visible degrees of freedom in a simple manner, yet still reproduce the complex correlations between visible degrees in the data once marginalized over (integrated out).

The network parameters, to be optimized/learned:

\(\mathbf{a}\) represents the visible bias, a vector of same length as \(\mathbf{x}\).

\(\mathbf{b}\) represents the hidden bias, a vector of same lenght as \(\mathbf{h}\).

\(W\) represents the interaction weights, a matrix of size \(M\times N\).

Joint distribution#

The restricted Boltzmann machine is described by a Boltzmann distribution

where \(Z\) is the normalization constant or partition function, defined as

It is common to ignore \(T_0\) by setting it to one.

Network Elements, the energy function#

The function \(E(\mathbf{x},\mathbf{h})\) gives the energy of a configuration (pair of vectors) \((\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{h})\). The lower the energy of a configuration, the higher the probability of it. This function also depends on the parameters \(\mathbf{a}\), \(\mathbf{b}\) and \(W\). Thus, when we adjust them during the learning procedure, we are adjusting the energy function to best fit our problem.

An expression for the energy function is

Here \(\beta_j^d(h_j)\) and \(\alpha_i^a(x_j)\) are so-called transfer functions that map a given input value to a desired feature value. The labels \(a\) and \(d\) denote that there can be multiple transfer functions per variable. The first sum depends only on the visible units. The second on the hidden ones. Note that there is no connection between nodes in a layer.

The quantities \(b\) and \(c\) can be interpreted as the visible and hidden biases, respectively.

The connection between the nodes in the two layers is given by the weights \(w_{ij}\).

Defining different types of RBMs#

There are different variants of RBMs, and the differences lie in the types of visible and hidden units we choose as well as in the implementation of the energy function \(E(\mathbf{x},\mathbf{h})\).

Binary-Binary RBM:

RBMs were first developed using binary units in both the visible and hidden layer. The corresponding energy function is defined as follows:

where the binary values taken on by the nodes are most commonly 0 and 1.

Gaussian-Binary RBM:

Another varient is the RBM where the visible units are Gaussian while the hidden units remain binary:

More about RBMs#

Useful when we model continuous data (i.e., we wish \(\mathbf{x}\) to be continuous)

Requires a smaller learning rate, since there’s no upper bound to the value a component might take in the reconstruction

Other types of units include:

Softmax and multinomial units

Gaussian visible and hidden units

Binomial units

Rectified linear units

To read more, see Lectures on Boltzmann machines in Physics.

Autoencoders: Overarching view#

Autoencoders are artificial neural networks capable of learning efficient representations of the input data (these representations are called codings) without any supervision (i.e., the training set is unlabeled). These codings typically have a much lower dimensionality than the input data, making autoencoders useful for dimensionality reduction.

More importantly, autoencoders act as powerful feature detectors, and they can be used for unsupervised pretraining of deep neural networks.

Lastly, they are capable of randomly generating new data that looks very similar to the training data; this is called a generative model. For example, you could train an autoencoder on pictures of faces, and it would then be able to generate new faces. Surprisingly, autoencoders work by simply learning to copy their inputs to their outputs. This may sound like a trivial task, but we will see that constraining the network in various ways can make it rather difficult. For example, you can limit the size of the internal representation, or you can add noise to the inputs and train the network to recover the original inputs. These constraints prevent the autoencoder from trivially copying the inputs directly to the outputs, which forces it to learn efficient ways of representing the data. In short, the codings are byproducts of the autoencoder’s attempt to learn the identity function under some constraints.

See also A. Geron’s textbook, chapter 15.

Bayesian Machine Learning#

This is an important topic if we aim at extracting a probability distribution. This gives us also a confidence interval and error estimates.

Bayesian machine learning allows us to encode our prior beliefs about what those models should look like, independent of what the data tells us. This is especially useful when we don’t have a ton of data to confidently learn our model.

Video on Bayesian deep learning

See also the slides here.

Reinforcement Learning#

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is one of the most exciting fields of Machine Learning today, and also one of the oldest. It has been around since the 1950s, producing many interesting applications over the years.

It studies how agents take actions based on trial and error, so as to maximize some notion of cumulative reward in a dynamic system or environment. Due to its generality, the problem has also been studied in many other disciplines, such as game theory, control theory, operations research, information theory, multi-agent systems, swarm intelligence, statistics, and genetic algorithms.

In March 2016, AlphaGo, a computer program that plays the board game Go, beat Lee Sedol in a five-game match. This was the first time a computer Go program had beaten a 9-dan (highest rank) professional without handicaps. AlphaGo is based on deep convolutional neural networks and reinforcement learning. AlphaGo’s victory was a major milestone in artificial intelligence and it has also made reinforcement learning a hot research area in the field of machine learning.

Lecture on Reinforcement Learning.

See also A. Geron’s textbook, chapter 16.

Transfer learning#

The goal of transfer learning is to transfer the model or knowledge obtained from a source task to the target task, in order to resolve the issues of insufficient training data in the target task. The rationality of doing so lies in that usually the source and target tasks have inter-correlations, and therefore either the features, samples, or models in the source task might provide useful information for us to better solve the target task. Transfer learning is a hot research topic in recent years, with many problems still waiting to be studied.

Adversarial learning#

The conventional deep generative model has a potential problem: the model tends to generate extreme instances to maximize the probabilistic likelihood, which will hurt its performance. Adversarial learning utilizes the adversarial behaviors (e.g., generating adversarial instances or training an adversarial model) to enhance the robustness of the model and improve the quality of the generated data. In recent years, one of the most promising unsupervised learning technologies, generative adversarial networks (GAN), has already been successfully applied to image, speech, and text.

Dual learning#

Dual learning is a new learning paradigm, the basic idea of which is to use the primal-dual structure between machine learning tasks to obtain effective feedback/regularization, and guide and strengthen the learning process, thus reducing the requirement of large-scale labeled data for deep learning. The idea of dual learning has been applied to many problems in machine learning, including machine translation, image style conversion, question answering and generation, image classification and generation, text classification and generation, image-to-text, and text-to-image.

Distributed machine learning#

Distributed computation will speed up machine learning algorithms, significantly improve their efficiency, and thus enlarge their application. When distributed meets machine learning, more than just implementing the machine learning algorithms in parallel is required.

Meta learning#

Meta learning is an emerging research direction in machine learning. Roughly speaking, meta learning concerns learning how to learn, and focuses on the understanding and adaptation of the learning itself, instead of just completing a specific learning task. That is, a meta learner needs to be able to evaluate its own learning methods and adjust its own learning methods according to specific learning tasks.

The Challenges Facing Machine Learning#

While there has been much progress in machine learning, there are also challenges.

For example, the mainstream machine learning technologies are black-box approaches, making us concerned about their potential risks. To tackle this challenge, we may want to make machine learning more explainable and controllable. As another example, the computational complexity of machine learning algorithms is usually very high and we may want to invent lightweight algorithms or implementations. Furthermore, in many domains such as physics, chemistry, biology, and social sciences, people usually seek elegantly simple equations (e.g., the Schrödinger equation) to uncover the underlying laws behind various phenomena. In the field of machine learning, can we reveal simple laws instead of designing more complex models for data fitting? Although there are many challenges, we are still very optimistic about the future of machine learning. As we look forward to the future, here are what we think the research hotspots in the next ten years will be.

See the article on Discovery of Physics From Data: Universal Laws and Discrepancies

Explainable machine learning#

Machine learning, especially deep learning, evolves rapidly. The ability gap between machine and human on many complex cognitive tasks becomes narrower and narrower. However, we are still in the very early stage in terms of explaining why those effective models work and how they work.

What is missing: the gap between correlation and causation. Standard Machine Learning is based on what e have called a frequentist approach.

Most machine learning techniques, especially the statistical ones, depend highly on correlations in data sets to make predictions and analyses. In contrast, rational humans tend to reply on clear and trustworthy causality relations obtained via logical reasoning on real and clear facts. It is one of the core goals of explainable machine learning to transition from solving problems by data correlation to solving problems by logical reasoning.

Bayesian Machine Learning is one of the exciting research directions in this field.

Quantum machine learning#

Quantum machine learning is an emerging interdisciplinary research area at the intersection of quantum computing and machine learning.

Quantum computers use effects such as quantum coherence and quantum entanglement to process information, which is fundamentally different from classical computers. Quantum algorithms have surpassed the best classical algorithms in several problems (e.g., searching for an unsorted database, inverting a sparse matrix), which we call quantum acceleration.

When quantum computing meets machine learning, it can be a mutually beneficial and reinforcing process, as it allows us to take advantage of quantum computing to improve the performance of classical machine learning algorithms. In addition, we can also use the machine learning algorithms (on classic computers) to analyze and improve quantum computing systems.

Read interview with Maria Schuld on her work on Quantum Machine Learning. See also her recent textbook.

Quantum machine learning algorithms based on linear algebra#

Many quantum machine learning algorithms are based on variants of quantum algorithms for solving linear equations, which can efficiently solve N-variable linear equations with complexity of O(log2 N) under certain conditions. The quantum matrix inversion algorithm can accelerate many machine learning methods, such as least square linear regression, least square version of support vector machine, Gaussian process, and more. The training of these algorithms can be simplified to solve linear equations. The key bottleneck of this type of quantum machine learning algorithms is data input—that is, how to initialize the quantum system with the entire data set. Although efficient data-input algorithms exist for certain situations, how to efficiently input data into a quantum system is as yet unknown for most cases.

Quantum reinforcement learning#

In quantum reinforcement learning, a quantum agent interacts with the classical environment to obtain rewards from the environment, so as to adjust and improve its behavioral strategies. In some cases, it achieves quantum acceleration by the quantum processing capabilities of the agent or the possibility of exploring the environment through quantum superposition. Such algorithms have been proposed in superconducting circuits and systems of trapped ions.

Quantum deep learning#

Dedicated quantum information processors, such as quantum annealers and programmable photonic circuits, are well suited for building deep quantum networks. The simplest deep quantum network is the Boltzmann machine. The classical Boltzmann machine consists of bits with tunable interactions and is trained by adjusting the interaction of these bits so that the distribution of its expression conforms to the statistics of the data. To quantize the Boltzmann machine, the neural network can simply be represented as a set of interacting quantum spins that correspond to an adjustable Ising model. Then, by initializing the input neurons in the Boltzmann machine to a fixed state and allowing the system to heat up, we can read out the output qubits to get the result.

The last words?#

Early computer scientist Alan Kay said, The best way to predict the future is to create it. Therefore, all machine learning practitioners, whether scholars or engineers, professors or students, need to work together to advance these important research topics. Together, we will not just predict the future, but create it.

Best wishes to you all and thanks so much for your heroic efforts this semester#

Figure 1:

Social machine learning#

Machine learning aims to imitate how humans learn. While we have developed successful machine learning algorithms, until now we have ignored one important fact: humans are social. Each of us is one part of the total society and it is difficult for us to live, learn, and improve ourselves, alone and isolated. Therefore, we should design machines with social properties. Can we let machines evolve by imitating human society so as to achieve more effective, intelligent, interpretable “social machine learning”?

And much more.